Low testosterone (a.k.a. “low T”) is caused by worn out glands no longer able to secrete enough T, right? At least this seems to be the most prevalent theory today, a theory that reminds me a lot of the “tired pancreas” theory () of diabetes. I should note that this low T problem, as it is currently presented, is one that affects almost exclusively men, particularly middle-aged men, not women. This is so even though T plays an important role in women’s health.

There are many studies that show associations between T levels and all kinds of diseases in men. But here is a problem with hormones: often several hormones vary together and in a highly correlated fashion. If you rely on statistics to reach conclusions, you must use techniques that allow you to rule out confounders; otherwise you may easily reach wrong conclusions. Examples are multivariate techniques that are sensitive to Simpson’s paradox and nonlinear algorithms; both of which are employed, by the way, by modern software tools such as WarpPLS (). Unfortunately, these are rarely, if ever, used in health-related studies.

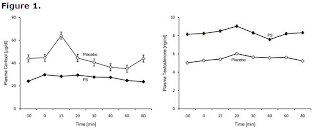

Many low T cases may actually be caused by something other than tired T-secretion glands, perhaps a hormone (or set of hormones) that suppress T production; a T “antagonist”. What would be a good candidate? The figure below shows two graphs. It is from a study by Starks and colleagues, published in the Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition in 2008 (). The study itself is not directly related to the main point that this post tries to make, but the figure is.

Look at the two graphs carefully. The one on the left is of blood cortisol levels. The one on the right is of blood testosterone levels. Ignore the variation within each graph. Just compare the two graphs and you will see one interesting thing – cortisol and testosterone levels are inversely related. This is a general pattern in connection with stress-induced cortisol elevations, repeating itself over and over again, whether the source of stress is mental (e.g., negative thoughts) or physical (e.g., intense exercise).

And the relationship between cortisol and testosterone is strong. Roughly speaking, an increase in cortisol levels, from about 20 to 40 μg/dl, appears to bring testosterone levels down from about 8 to 5 ηg/ml. A level of 8 ηg/ml (the same as 800 ηg/dl) is what is normally found in young men living in urban environments. A level of 5 ηg/ml is what is normally found in older men living in urban environments.

So, testosterone levels are practically brought down to almost half of what they were before by that variation in cortisol.

Chronic stress can easily bring your cortisol levels up to 40 μg/dl and keep them there. More serious pathological conditions, such as Cushing’s disease, can lead to sustained cortisol levels that are twice as high. There are many other things that can lead to chronically elevated cortisol levels. For instance, sustained calorie restriction raises cortisol levels, with a corresponding reduction in testosterone levels. As the authors of a study () of markers of semistarvation in healthy lean men note, grimly:

“…testosterone (T) approached castrate levels …”

The study highlights a few important phenomena that occur under stress conditions: (a) cortisol levels go up, and testosterone levels go down, in a highly correlated fashion (as mentioned earlier); and (b) it is very difficult to suppress cortisol levels without addressing the source of the stress. Even with testosterone administration, cortisol levels tend to be elevated.

Isn't possible that cortisol levels go up because testosterone levels go down - reverse causality? Possible, but unlikely. Evidence that testosterone administration may reduce cortisol levels, when it is found, tends to be rather weak or inconclusive. A good example is a study by Rubinow and colleagues (). Not only were their findings based on bivariate (or unadjusted) correlations, but also on a chance probability threshold that is twice the level usually employed in statistical analyses; the level usually employed is 5 percent.

Let us now briefly shift our attention to dieting. Dieting is the main source of calorie restriction in modern urban societies; an unnatural one, I should say, because it involves going hungry in the presence of food. Different people have different responses to dieting. Some responses are more extreme, others more mild. One main factor is how much body fat you want to lose (weight loss, as a main target, is a mistake); another is how low you expect body fat to get. Many men dream about six-pack abs, which usually require single-digit body fat percentages.

The type of transformation involving going from obese to lean is not “cost-free”, as your body doesn’t know that you are dieting. The body “sees” starvation, and responds accordingly.

Your body is a little bit like a computer. It does exactly what you “tell” it to do, but often not what you want it to do. In other words, it responds in relatively predictable ways to various diet and lifestyle changes, but not in the way that most of us want. This is what I call compensatory adaptation at work (). Our body often doesn’t respond in the way we expect either, because we don’t actually know how it adapts; this is especially true for long-term adaptations.

What initially feels like a burst of energy soon turns into something a bit more unpleasant. At first the unpleasantness takes the form of psychological phenomena, which were probably the “cheapest” for our bodies to employ in our evolutionary past. Feeling irritated is not as “expensive” a response as feeling physically weak, seriously distracted, nauseated etc. if you live in an environment where you don’t have the option of going to the grocery store to find fuel, and where there are many beings around that can easily kill you.

Soon the responses take the form of more nasty body sensations. Nearly all of those who go from obese to lean will experience some form of nasty response over time. The responses may be amplified by nutrient deficiencies. Obesity would have probably only been rarely, if ever, experienced by our Paleolithic ancestors. They would have never gotten obese in the first place. Going from obese to lean is as much a Neolithic novelty as becoming obese in the first place, although much less common.

And it seems that those who have a tendency toward mental disorders (e.g., generalized anxiety, manic-depression), even if at a subclinical level under non-dieting conditions, are the ones that suffer the most when calorie restriction is sustained over long periods of time. Most reports of serious starvation experiments (e.g., Roy Walford’s Biosphere 2 experiment) suggest the surfacing of mental disorders and even some cases of psychosis.

Emily Deans has a nice post () on starvation and mental health.

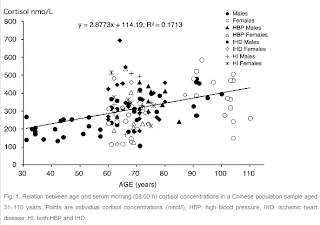

But you may ask: What if my low T problem is caused by aging; you just said that older males tend to have lower T? To which I would reply: Isn’t possible that the lower T levels normally associated with aging are in many cases a byproduct of higher stress hormone levels? Take a look at the figure below, from a study of age-related cortisol secretion by Zhao and colleagues ().

As you can see in the figure, cortisol levels tend to go up with age. And, interestingly, the range of variation seems very close to that in the earlier figure in this post, although I may be making a mistake in the conversion from nmol/l to ηg/ml. As cortisol levels go up, T levels should go down in response. There are outliers. Note the male outlier at the middle-bottom part, in his early seventies. He is represented by a filled circle, which refers to a disease-free male.

Dr. Arthur De Vany claims to have high T levels in his 70s. It is possible that he is like that outlier. If you check out De Vany’s writings, you’ll see his emphasis on leading a peaceful, stress-free, life (). If money, status, material things, health issues etc. are very important for you when you are young (most of us, a trend that seems to be increasing), chances are they are going to be a major source of stress as you age.

Think about individual property accumulation, as it is practiced in modern urban environments, and how unnatural and potentially stressful it is. Many people subconsciously view their property (e.g., a nice car, a bunch of shares in a publicly-traded company) as their extended phenotype. If that property is damaged or loses value, the subconscious mental state evoked is somewhat like that in response to a piece of their body being removed. This is potentially very stressful; a stress source that doesn’t go away easily. What we have here is very different from the types of stress that our Paleolithic ancestors faced.

So, what will happen if you take testosterone supplementation to solve your low T problem? If your problem is due to high levels of cortisol and other stress hormones (including some yet to be discovered), induced by stress, and your low T treatment is long-term, your body will adapt in a compensatory way. It will “sense” that T is now high, together with high levels of stress.

Whatever form long-term compensatory adaptation may take in this scenario, somehow the combination of high T and high stress doesn’t conjure up a very nice image. What comes to mind is a borderline insane person, possibly with good body composition, and with a lot of self-confidence – someone like the protagonist of the film American Psycho.

Again, will the high T levels, obtained through supplementation, suppress cortisol? It doesn’t seem to work that way, at least not in the long term. In fact, stress hormones seem to affect other hormones a lot more than other hormones affect them. The reason is probably that stress responses were very important in our evolutionary past, which would make any mechanism that could override them nonadaptive.

Today, stress hormones, while necessary for a number of metabolic processes (e.g., in intense exercise), often work against us. For example, serious conflict in our modern world is often solved via extensive writing (through legal avenues). Violence is regulated and/or institutionalized – e.g., military, law enforcement, some combat sports. Without these, society would break down, and many of us would join the afterlife sooner and more violently than we would like (see Pinker’s take on this topic: ).

Sir, the solution to your low T problem may actually be found elsewhere, namely in stress reduction. But careful, you run the risk of becoming a nice guy.