Let me start this post by telling you that my interview with Jimmy Moore is coming up in about a week. Jimmy and I talk about evolution, statistics, and health – the main themes of this blog. We talk also about other things, and probably do not agree on everything. The interview was actually done a while ago, so I don’t remember exactly what we discussed.

From what I remember from mine and other interviews (I listen to Jimmy's podcasts regularly), I think I am the guest who has mentioned the most people during an interview – Gary Taubes, Chris Masterjohn, Carbsane, Petro (a.k.a., Peter “the Hyperlipid”), T. Colin Campbell, Denise Minger, Kurt Harris, Stephan Guyenet, Art De Vany, and a few others. What was I thinking?

In case you listen and wonder, my accent is a mix of Brazilian Portuguese, New Zealand English (where I am called “Need”), American English, and the dialect spoken in the “country” of Texas. The strongest influences are probably American English and Brazilian Portuguese.

Anyway, when medical doctors (MDs) look at someone’s lipid panel, one single number tends to draw their attention: the LDL cholesterol. That is essentially the amount of cholesterol in LDL particles.

One’s LDL cholesterol is a reflection of many factors, including: diet, amount of cholesterol produced by the liver, amount of cholesterol actually used by your body, amount of cholesterol recycled by the liver, and level of systemic inflammation. This number is usually calculated, and often very different from the number you get through a VAP test.

It is not uncommon for a high saturated fat diet to lead to a benign increase in LDL cholesterol. In this case the LDL particles will be large, which will also be reflected in a low “fasting triglycerides number” (lower than 70 mg/dl). While I say "benign" here, which implies a neutral effect on health, an increase in LDL cholesterol in this context may actually be health promoting.

Large LDL particles are less likely to cross the gaps in the endothelium, the thin layer of cells that lines the interior surface of blood vessels, and form atheromatous plaques.

Still, when an MD sees an LDL cholesterol higher than 100 mg/dl, more often than not he or she will tell you that it is bad news. Whether that is bad news or not is really speculation, even for high LDL numbers. A more reliable approach is to check one’s arteries directly. Interestingly, atheromatous plaques only form in arteries, not in veins.

The figure below (from: Novogen.com) shows a photomicrograph of carotid arteries from rabbits, which are very similar, qualitatively speaking, to those of humans. The meanings of the letters are: L = lumen; I = intima; M = media; and A = adventitia. The one on the right has significantly lower intima-media (I-M) thickness than the one on the left.

Atherosclerosis in humans tends to lead to an increase in I-M thickness; the I-M area being normally where atheromatous plaques grow. Aging also leads to an increase in I-M thickness. Typically one’s risk of premature death from cardiovascular complications correlates with one’s I-M thickness’ “distance” from that of low-risk individuals in the same sex and age group.

This notion has led to the coining of the term “vascular age”. For example, someone may be 30 years old, but have a vascular age of 80, meaning that his or her I-M thickness is that of an average 80-year-old. Conversely, someone may be 80 and have a vascular age of 30.

Nearly everybody’s I-M thickness goes up with age, even people who live to be 100 or more. Incidentally, this is true for average blood glucose levels as well. In long-living people they both go up slowly.

I-M thickness tests are noninvasive, based on external ultrasound, and often covered by health insurance. They take only a few minutes to conduct. Their reports provide information about one’s I-M thickness and its relative position in the same sex and age group, as well as the amount of deposited plaque. The latter is frequently provided as a bonus, since it can also be inferred with reasonable precision from the computer images generated via ultrasound.

Below is the top part of a typical I-M thickness test report (from: Sonosite.com). It shows a person’s average (or mean) I-M thickness; the red dot on the graph. The letter notations (A … E) are for reference groups. For the majority of the folks doing this test, the most important on this report are the thick and thin lines indicated as E, which are based on Aminbakhsh and Mancini’s (1999) study.

The reason why the thick and thin lines indicated as E are the most important for the majority of folks taking this test is that they are based on a study that provides one of the best reference ranges for people who are 45 and older, who are usually the ones getting their I-M thickness tested. Roughly speaking, if your red dot is above the thin line, you are at increased risk of cardiovascular disease.

Most people will fall in between the thick and thin lines. Those below the thick line (with the little blue triangles) are at very low risk, especially if they have little to no plaque. The person for whom this test was made is at very low risk. His red dot is below the thick line, when that line is extended to the little triangle indicated as D.

Below is the bottom part of the I-M thickness test report. The max I-M thickness score shown here tends to add little in terms of diagnosis to the mean score shown earlier. Here the most important part is the summary, under “Comments”. It says that the person has no plaque, and is at a lower risk of heart attack. If you do an I-M thickness test, your doctor will probably be able to tell you more about these results.

I like numbers, so I had an I-M thickness test done recently on me. When the doctor saw the results, which we discussed, he told me that he could guarantee two things: (1) I would die; and (2) but not of heart disease. MDs have an interesting sense of humor; just hang out with a group of them during a “happy hour” and you’ll see.

My red dot was below the thick line, and I had a plaque measurement of zero. I am 47 years old, eat about 1 lb of meat per day, and around 20 eggs per week - with the yolk. About half of the meat I eat comes from animal organs (mostly liver) and seafood. I eat organ meats about once a week, and seafood three times a week. This is an enormous amount of dietary cholesterol, by American diet standards. My saturated fat intake is also high by the same standards.

You can check the post on my transformation to see what I have been doing for years now, and some of the results in terms of levels of energy, disease, and body fat levels. Keep in mind that mine are essentially the results of a single-individual experiment; results that clearly contradict the lipid hypothesis. Still, they are also consistent with a lot of fairly reliable empirical research.

Monday, May 30, 2011

Friday, May 27, 2011

Fitness, hunter-gatherer style

|

| Aché man hunting. Credit: Wiki |

“So the bottom line is that foragers are often in good shape and they look it. They sprint, jog, climb, carry, jump, etc all day long but are not specialists.”The quote above is excerpted from a description given by anthropologist Kim Hill (whose work I've previously written about here) of his experience observing the behaviors of the Aché of Paraguay and the Hiwi of Venezuela. The ASU professor, who has been living and studying the tribes for more than 30 years, recently had his work highlighted in a commentary published in Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases.

The article, whose lead author was James O'Keefe, MD, examines the daily physical activity patterns among hunter gatherers and fossil hominins. According to the authors, ancestral hunter-gatherers expended as much as five times more amounts of energy on physical activity than the average modern sedentary adult.

Based on data from Cordain's earlier work and that of colleagues, the article proposes a cross-training exercise regimen, as opposed to specialized trainings of Olympic athletes, intended to mimic the way of life that is required of a typical hunter gatherer. The "prescription for organic fitness" includes 14 essential features, which the authors suggest "appear to be ideal for developing and maintaining fitness and general health while reducing risk of injury."

Summarily, here they are:

- Walk or run 3 to 10 miles a day.

- After a strenuous day, take a rest day.

- Take it easy on your joints. Walk or run on grass or dirt, not asphalt.

- Walk or run barefoot or in leather slippers. Shoes lead to injuries.

- Once or twice a week, do interval training. This involves short bursts of intense exercise like sprints.

- Focus on a variety of exercises: Weights, cardio, and stretching.

- Carry a child, a log, a rock. It builds muscle and bone.

- Stay lean. In other words, don't eat too much. It can lead to inflammation and cause problems for your joints.

- Exercise outside. Take advantage of some vitamin D.

- Socialize while exercising. Like our ancestors did when hunting and foraging.

- Walk with your dog. Dogs have been a companion to man for at least 150,000 years.

- Dance like a wild human.

- Have wild sex.

- Sleep, or rest, after any of the above activities.

Source: O'Keefe JH, Vogel R, Lavie CJ, and Cordain L. Exercise Like a Hunter-Gatherer: A Prescription for Organic Physical Fitness. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2011;53:471-9. doi:10.1016/j.pcad.2011.03.009.

Note: With exception of Hill's description of his experience among hunter-gatherers, most of what's in the new article is identical to what was published last year by the same authors in The Physician and Sports Medicine found here.

Networking, Dementia, Australia and a Breakthrough...

Networking Evening

I just want to say a big thank you to everyone who came along last night and took part in this session. I really enjoyed the very animated conversation and am keen to take some of the ideas we discussed forward. For those of you who didn't attend the ares we really got to grips with were focused on the relationship between artists who work in the broad field of Arts/Health and colleagues in the Arts Therapy field. An outcome of this discussion will be to form a small group who'll pull together a statement that best encapsulates this relationship allowing for synergy and difference, but crucially, offering dialogue and mutuality.

We had some very passionate and interesting discussions around dementia and the arts and I'm sure all who came along last night would want to give a huge thanks to Zoe Keenan who shared her personal experiences around caring for her mum and her creative response to this experience. On the basis of this exciting work and suggestions form the group, we are going to explore some very interesting work in the region. I very much look forward to our next meeting and thanks again for everyone in making this such an enjoyable and inspirational evening.

Australia Calling

I am thrilled to be speaking at this conference. If you want to know more about it, or hear from Arts for Health Australia’s inspirational leader, please come along and meet Margret Meagher at the Head to Head here at MMU on June 30th (full details over the next two weeks). My paper this year at the Canberra conference will explore the relationship between Design, the Arts and Health with a specific focus on how the last days of our lives are often far removed than what we’d hope they might be like.

3rd Annual International Arts and Health Conference:

The Art of Good Health and Wellbeing

14 - 18 November 2011

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT

The Art of Good Health and Wellbeing, 3rd Annual International Arts and Health Conference, will present best practice and innovative arts and health programs, effective health promotion and prevention campaigns, methods of project evaluation and scientific research. The 2011 Conference will continue to have a special focus on mental health and creative ageing, including programs for people with dementia and their carers; as well as workplace wellbeing programs; arts and health programs for Aboriginal communities; the built environment, design and health; medical education and medical humanities. http://www.artsandhealth.org/

Breakthrough: Art in Mental Health

Damian Hebron and Mike Farrer will both be speaking at Breakthrough’s third ARTS in Health Event:

‘Where to Next…?’

Location : NHS North West, 3 Piccadilly Place, Manchester

Date: 10th of June, 2011. 9:30-3pm

http://breakthroughmhart.com/

Towards a National Forum for Arts and Health Many of you will know that I sit on a group that has been looking at the notion of a National Forum for Arts and Health, following the collapse of the NNAH in 2007. I’ve been working with colleagues around the country to explore ways forward, and the linked report has been made by the external consultants Globe to help inform this direction. I would be grateful for any thoughts on this linked document, which I will feed into the forum at our next meeting. http://www.artsforhealth.org/resources/final_national_forum_report.pdf

If you would like me to email a copy of the SUMMARY REPORT, please email me directly.

I just want to say a big thank you to everyone who came along last night and took part in this session. I really enjoyed the very animated conversation and am keen to take some of the ideas we discussed forward. For those of you who didn't attend the ares we really got to grips with were focused on the relationship between artists who work in the broad field of Arts/Health and colleagues in the Arts Therapy field. An outcome of this discussion will be to form a small group who'll pull together a statement that best encapsulates this relationship allowing for synergy and difference, but crucially, offering dialogue and mutuality.

We had some very passionate and interesting discussions around dementia and the arts and I'm sure all who came along last night would want to give a huge thanks to Zoe Keenan who shared her personal experiences around caring for her mum and her creative response to this experience. On the basis of this exciting work and suggestions form the group, we are going to explore some very interesting work in the region. I very much look forward to our next meeting and thanks again for everyone in making this such an enjoyable and inspirational evening.

I am thrilled to be speaking at this conference. If you want to know more about it, or hear from Arts for Health Australia’s inspirational leader, please come along and meet Margret Meagher at the Head to Head here at MMU on June 30th (full details over the next two weeks). My paper this year at the Canberra conference will explore the relationship between Design, the Arts and Health with a specific focus on how the last days of our lives are often far removed than what we’d hope they might be like.

|

| “The Aboriginal Memorial 1987-88, Ramingining Artists, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, photographer credit John Gollings |

The Art of Good Health and Wellbeing

14 - 18 November 2011

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, ACT

The Art of Good Health and Wellbeing, 3rd Annual International Arts and Health Conference, will present best practice and innovative arts and health programs, effective health promotion and prevention campaigns, methods of project evaluation and scientific research. The 2011 Conference will continue to have a special focus on mental health and creative ageing, including programs for people with dementia and their carers; as well as workplace wellbeing programs; arts and health programs for Aboriginal communities; the built environment, design and health; medical education and medical humanities. http://www.artsandhealth.org/

Breakthrough: Art in Mental Health

Damian Hebron and Mike Farrer will both be speaking at Breakthrough’s third ARTS in Health Event:

‘Where to Next…?’

Location : NHS North West, 3 Piccadilly Place, Manchester

Date: 10th of June, 2011. 9:30-3pm

http://breakthroughmhart.com/

If you would like me to email a copy of the SUMMARY REPORT, please email me directly.

Monday, May 23, 2011

The China Study II: Wheat may not be so bad if you eat 221 g or more of animal food daily

In previous posts on this blog covering the China Study II data we’ve looked at the competing effects of various foods, including wheat and animal foods. Unfortunately we have had to stick to the broad group categories available from the specific data subset used; e.g., animal foods, instead of categories of animal foods such as dairy, seafood, and beef. This is still a problem, until I can find the time to get more of the China Study II data in a format that can be reliably used for multivariate analyses.

What we haven’t done yet, however, is to look at moderating effects. And that is something we can do now. A moderating effect is the effect of a variable on the effect of another variable on a third. Sounds complicated, but WarpPLS makes it very easy to test moderating effects. All you have to do is to make a variable (e.g., animal food intake) point at a direct link (e.g., between wheat flour intake and mortality). The moderating effect is shown on the graph as a dashed arrow going from a variable to a link between two variables.

The graph below shows the results of an analysis where animal food intake (Afoods) is hypothesized to moderate the effects of wheat flour intake (Wheat) on mortality in the 35 to 69 age range (Mor35_69) and mortality in the 70 to 79 age range (Mor70_79). A basic linear algorithm was used, whereby standardized partial regression coefficients, both moderating and direct, are calculated based on the equations of best-fitting lines.

From the graph above we can tell that wheat flour intake increases mortality significantly in both age ranges; in the 35 to 69 age range (beta=0.17, P=0.05), and in the 70 to 79 age range (beta=0.24, P=0.01). This is a finding that we have seen before on previous posts, and that has been one of the main findings of Denise Minger’s analysis of the China Study data. Denise and I used different data subsets and analysis methods, and reached essentially the same results.

But here is what is interesting about the moderating effects analysis results summarized on the graph above. They suggest that animal food intake significantly reduces the negative effect of wheat flour consumption on mortality in the 70 to 79 age range (beta=-0.22, P<0.01). This is a relatively strong moderating effect. The moderating effect of animal food intake is not significant for the 35 to 69 age range (beta=-0.00, P=0.50); the beta here is negative but very low, suggesting a very weak protective effect.

Below are two standardized plots showing the relationships between wheat flour intake and mortality in the 70 to 79 age range when animal food intake is low (left plot) and high (right plot). As you can see, the best-fitting line is flat on the right plot, meaning that wheat flour intake has no effect on mortality in the 70 to 79 age range when animal food intake is high. When animal food intake is low (left plot), the effect of wheat flour intake on mortality in this range is significant; its strength is indicated by the upward slope of the best-fitting line.

What these results seem to be telling us is that wheat flour consumption contributes to early death for several people, perhaps those who are most sensitive or intolerant to wheat. These people are represented in the variable measuring mortality in the 35 to 69 age range, and not in the 70 to 79 age range, since they died before reaching the age of 70.

Those in the 70 to 79 age range may be the least sensitive ones, and for whom animal food intake seems to be protective. But only if animal food intake is above a certain level. This is not a ringing endorsement of wheat, but certainly helps explain wheat consumption in long-living groups around the world, including the French.

How much animal food does it take for the protective effect to be observed? In the China Study II sample, it is about 221 g/day or more. That is approximately the intake level above which the relationship between wheat flour intake and mortality in the 70 to 79 age range becomes statistically indistinguishable from zero. That is a little less than ½ lb, or 7.9 oz, of animal food intake per day.

What we haven’t done yet, however, is to look at moderating effects. And that is something we can do now. A moderating effect is the effect of a variable on the effect of another variable on a third. Sounds complicated, but WarpPLS makes it very easy to test moderating effects. All you have to do is to make a variable (e.g., animal food intake) point at a direct link (e.g., between wheat flour intake and mortality). The moderating effect is shown on the graph as a dashed arrow going from a variable to a link between two variables.

The graph below shows the results of an analysis where animal food intake (Afoods) is hypothesized to moderate the effects of wheat flour intake (Wheat) on mortality in the 35 to 69 age range (Mor35_69) and mortality in the 70 to 79 age range (Mor70_79). A basic linear algorithm was used, whereby standardized partial regression coefficients, both moderating and direct, are calculated based on the equations of best-fitting lines.

From the graph above we can tell that wheat flour intake increases mortality significantly in both age ranges; in the 35 to 69 age range (beta=0.17, P=0.05), and in the 70 to 79 age range (beta=0.24, P=0.01). This is a finding that we have seen before on previous posts, and that has been one of the main findings of Denise Minger’s analysis of the China Study data. Denise and I used different data subsets and analysis methods, and reached essentially the same results.

But here is what is interesting about the moderating effects analysis results summarized on the graph above. They suggest that animal food intake significantly reduces the negative effect of wheat flour consumption on mortality in the 70 to 79 age range (beta=-0.22, P<0.01). This is a relatively strong moderating effect. The moderating effect of animal food intake is not significant for the 35 to 69 age range (beta=-0.00, P=0.50); the beta here is negative but very low, suggesting a very weak protective effect.

Below are two standardized plots showing the relationships between wheat flour intake and mortality in the 70 to 79 age range when animal food intake is low (left plot) and high (right plot). As you can see, the best-fitting line is flat on the right plot, meaning that wheat flour intake has no effect on mortality in the 70 to 79 age range when animal food intake is high. When animal food intake is low (left plot), the effect of wheat flour intake on mortality in this range is significant; its strength is indicated by the upward slope of the best-fitting line.

What these results seem to be telling us is that wheat flour consumption contributes to early death for several people, perhaps those who are most sensitive or intolerant to wheat. These people are represented in the variable measuring mortality in the 35 to 69 age range, and not in the 70 to 79 age range, since they died before reaching the age of 70.

Those in the 70 to 79 age range may be the least sensitive ones, and for whom animal food intake seems to be protective. But only if animal food intake is above a certain level. This is not a ringing endorsement of wheat, but certainly helps explain wheat consumption in long-living groups around the world, including the French.

How much animal food does it take for the protective effect to be observed? In the China Study II sample, it is about 221 g/day or more. That is approximately the intake level above which the relationship between wheat flour intake and mortality in the 70 to 79 age range becomes statistically indistinguishable from zero. That is a little less than ½ lb, or 7.9 oz, of animal food intake per day.

Labels:

China Study,

longevity,

research,

statistics,

warppls

Thursday, May 19, 2011

Job opportunities, and an Opera

Fables – A Film Opera

VENUE: Zion Arts Centre, Hulme (screening and live theatrical event)

DATE & TIME: 30th June, 7-8pm

Step into a magical world of legend and folklore with Streetwise Opera’s Fables - A Film Opera, a group of four short films interspersed with live performance and theatre, created by some of the UK's leading composers and filmmakers working with 125 Streetwise performers who have experienced homelessness. Composers Mira Calix, Emily Hall, Orlando Gough and Paul Sartin/Andy Mellon, and filmmakers Gaëlle Denis, Tom Marshall, Flat-e and Iain Finlay have created short films based on traditional fables ranging from the classic The Boy Who Cried Wolf to Shinishi Hoshi's contemporary tale, Hey! Come on Out!

This special event at Zion Arts Centre is part of the fringe Not Part of Festival, and involves a screening of the films, around which there will be live performance and theatre created by director Emma Bernard and led by a sizzling folk musicians. They will be joined by Streetwise Opera’s award-winning singers from the Booth Centre in Manchester, the ICC in Nottingham and narrator Neil Allen. The evening will include some rousing opera, folk, hidden performers and uplifting audience participation.

More details HERE.

Arts and Health Practitioners required for exciting dementia project in Merseyside http://www.collective-encounters.org.uk/

VENUE: Zion Arts Centre, Hulme (screening and live theatrical event)

DATE & TIME: 30th June, 7-8pm

Step into a magical world of legend and folklore with Streetwise Opera’s Fables - A Film Opera, a group of four short films interspersed with live performance and theatre, created by some of the UK's leading composers and filmmakers working with 125 Streetwise performers who have experienced homelessness. Composers Mira Calix, Emily Hall, Orlando Gough and Paul Sartin/Andy Mellon, and filmmakers Gaëlle Denis, Tom Marshall, Flat-e and Iain Finlay have created short films based on traditional fables ranging from the classic The Boy Who Cried Wolf to Shinishi Hoshi's contemporary tale, Hey! Come on Out!

This special event at Zion Arts Centre is part of the fringe Not Part of Festival, and involves a screening of the films, around which there will be live performance and theatre created by director Emma Bernard and led by a sizzling folk musicians. They will be joined by Streetwise Opera’s award-winning singers from the Booth Centre in Manchester, the ICC in Nottingham and narrator Neil Allen. The evening will include some rousing opera, folk, hidden performers and uplifting audience participation.

More details HERE.

Arts and Health Practitioners required for exciting dementia project in Merseyside http://www.collective-encounters.org.uk/

Monday, May 16, 2011

How Neandertals Lived, Hunted, and Ate

This Discovery Channel series "Neanderthal" presents a wonderful re-enactment of how Neandertals lived in small groups, how they hunted together, and how they ate.

I was especially taken by how much we know about the way they used tools to butcher meat, scraped animal hides (by holding the hides in their teeth and face as a tool to spread the stress around the skull) for use in making clothing (shown in Part 1).

It's amazing that we know so much about these ancient peoples -- how strong they were, how intelligent, how adaptive, as said in the documentary.

The scientific techniques mentioned that lend to our understanding of Neandertals are studies on fossilized feces, worn-out teeth from scraping animal hides, and bone fractures that reveal injuries that led to illness or death.

New Neandertal Study

I wonder what changes will have to be realized to this documentary in light of new research from the Journal of Human Evolution. The linked article reports that new findings that Neandertals may have hunted in a manner more modern than ever thought beforehand.

Kate Britton and her team from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig, make these conclusions based on analysis of reindeer teeth strontium isotopes.

Strontium is an alkaline earth metal that is taken up into bones and teeth. The amount of strontium can shed light on how much food and water was consumed by the reindeer and humans, then also provides clues to what soil and rocks were about, suggesting whether or not the reindeer "ate and drank always in the same area, or if they moved around."

The reindeer's isotopes reveal that they were hunted close to a specific site, so it lends reason to the idea that Neandertals were "sophisticated" enough to "plan" stays around areas at certain times of the year (spring/autumn) based on reindeer migration patterns.

To think that Neandertals hunted like modern human groups is astounding, as it fosters more thought into what really happened that caused them to die out -- was it because of climate change, lack of food, the appearance of humans in Europe?

Study reference: Britton, K., et al., Strontium isotope evidence for migration in late Pleistocene Rangifer: Implications for Neanderthal hunting strategies at the Middle Palaeolithic site of Jonzac, France, Journal of Human Evolution (2011), doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.03.004

Labels:

evolution

Book review: Biology for Bodybuilders

The photos below show Doug Miller and his wife, Stephanie Miller. Doug is one of the most successful natural bodybuilders in the U.S.A. today. He is also a manager at an economics consulting firm and an entrepreneur. As if these were not enough, now he can add book author to his list of accomplishments. His book, Biology for Bodybuilders, has just been published.

Doug studied biochemistry, molecular biology, and economics at the undergraduate level. His co-authors are Glenn Ellmers and Kevin Fontaine. Glenn is a regular commenter on this blog, a professional writer, and a certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist. Dr. Fontaine is an Associate Professor at the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Biology for Bodybuilders is written in the first person by Doug, which is one of the appealing aspects of the book. This also allows Doug to say that his co-authors disagree with him sometimes, even as he outlines what works for him. Both Glenn and Kevin are described as following Paleolithic dieting approaches. Doug follows a more old school bodybuilding approach to dieting – e.g., he eats grains, and has multiple balanced meals everyday.

This relaxed approach to team writing neutralizes criticism from those who do not agree with Doug, at least to a certain extent. Maybe it was done on purpose; a smart idea. For example, I do not agree with everything Doug says in the book, but neither do Doug’s co-authors, by his own admission. Still, one thing we all have to agree with – from a competitive sports perspective, no one can question success.

At less than 120 pages, the book is certainly not encyclopedic, but it is quite packed with details about human physiology and metabolism for a book of this size. The scientific details are delivered in a direct and simple manner, through what I would describe as very good writing.

Doug has interesting ideas on how to push his limits as a bodybuilder. For example, he likes to train for muscle hypertrophy at around 20-30 lbs above his contest weight. Also, he likes to exercise at high repetition ranges, which many believe is not optimal for muscle growth. He does that even for mass building exercises, such as the deadlift. In this video he deadlifts 405 lbs for 27 repetitions.

Here it is important to point out that whether one is working out in the anaerobic range, which is where muscle hypertrophy tends to be maximized, is defined not by the number of repetitions but by the number of seconds a muscle group is placed under stress. The anaerobic range goes from around 20 to 120 seconds. If one does many repetitions, but does them fast, he or she will be in the anaerobic range. Incidentally, this is the range of strength training at which glycogen depletion is maximized.

I am not a bodybuilder, nor do I plan on becoming one, but I do admire athletes that excel in narrow sports. Also, I strongly believe in the health-promoting effects of moderate glycogen-depleting exercise, which includes strength training and sprints. Perhaps what top athletes like Doug do is not exactly optimal for long-term health, but it certainly beats sedentary behavior hands down. Or maybe top athletes will live long and healthy lives because the genetic makeup that allows them to be successful athletes is also conducive to great health.

In this respect, however, Doug is one of the people who have gotten the closest to convincing me that genes do not influence so much what one can achieve as a bodybuilder. In the book he shows a photo of himself at age 18, when he apparently weighed not much more than 135 lbs. Now, in his early 30s, he weighs 210-225 lbs during the offseason, at a height of 5'9". He has achieved this without taking steroids. Maybe he is a good example of compensatory adaptation, where obstacles lead to success.

If you are interested in natural bodybuilding, and/or the biology behind it, this book is highly recommended!

(Source: www.dougmillerpro.com)

Doug studied biochemistry, molecular biology, and economics at the undergraduate level. His co-authors are Glenn Ellmers and Kevin Fontaine. Glenn is a regular commenter on this blog, a professional writer, and a certified Strength and Conditioning Specialist. Dr. Fontaine is an Associate Professor at the Johns Hopkins University’s School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Biology for Bodybuilders is written in the first person by Doug, which is one of the appealing aspects of the book. This also allows Doug to say that his co-authors disagree with him sometimes, even as he outlines what works for him. Both Glenn and Kevin are described as following Paleolithic dieting approaches. Doug follows a more old school bodybuilding approach to dieting – e.g., he eats grains, and has multiple balanced meals everyday.

This relaxed approach to team writing neutralizes criticism from those who do not agree with Doug, at least to a certain extent. Maybe it was done on purpose; a smart idea. For example, I do not agree with everything Doug says in the book, but neither do Doug’s co-authors, by his own admission. Still, one thing we all have to agree with – from a competitive sports perspective, no one can question success.

At less than 120 pages, the book is certainly not encyclopedic, but it is quite packed with details about human physiology and metabolism for a book of this size. The scientific details are delivered in a direct and simple manner, through what I would describe as very good writing.

Doug has interesting ideas on how to push his limits as a bodybuilder. For example, he likes to train for muscle hypertrophy at around 20-30 lbs above his contest weight. Also, he likes to exercise at high repetition ranges, which many believe is not optimal for muscle growth. He does that even for mass building exercises, such as the deadlift. In this video he deadlifts 405 lbs for 27 repetitions.

Here it is important to point out that whether one is working out in the anaerobic range, which is where muscle hypertrophy tends to be maximized, is defined not by the number of repetitions but by the number of seconds a muscle group is placed under stress. The anaerobic range goes from around 20 to 120 seconds. If one does many repetitions, but does them fast, he or she will be in the anaerobic range. Incidentally, this is the range of strength training at which glycogen depletion is maximized.

I am not a bodybuilder, nor do I plan on becoming one, but I do admire athletes that excel in narrow sports. Also, I strongly believe in the health-promoting effects of moderate glycogen-depleting exercise, which includes strength training and sprints. Perhaps what top athletes like Doug do is not exactly optimal for long-term health, but it certainly beats sedentary behavior hands down. Or maybe top athletes will live long and healthy lives because the genetic makeup that allows them to be successful athletes is also conducive to great health.

In this respect, however, Doug is one of the people who have gotten the closest to convincing me that genes do not influence so much what one can achieve as a bodybuilder. In the book he shows a photo of himself at age 18, when he apparently weighed not much more than 135 lbs. Now, in his early 30s, he weighs 210-225 lbs during the offseason, at a height of 5'9". He has achieved this without taking steroids. Maybe he is a good example of compensatory adaptation, where obstacles lead to success.

If you are interested in natural bodybuilding, and/or the biology behind it, this book is highly recommended!

Wednesday, May 11, 2011

m a n i f e s t o update and much, much more...

Head to Head

In my last blog posting, I told you a little about the free event on June 30th that will see a host of international figures from the arts/health world, sharing some of their practice and engaging in conversation. I’ve been overwhelmed by the response and it looks like it will be fully booked well ahead of the event. I have to reiterate that I can’t guarantee anyone a place yet, but thanks for the emails. I will confirm places/agenda/venue/times at the beginning of June.

Towards a National Forum for Arts and Health

Many of you will know that I sit on a group that has been looking at the notion of a National Forum for Arts and Health, following the collapse of the NNAH in 2007. I’ve been working with colleagues around the country to explore ways forward, and the linked report has been made by the external consultants Globe to help inform this direction. I would be grateful for any thoughts on this linked document, which I will feed into the forum at our next meeting.

http://www.artsforhealth.org/resources/final_national_forum_report.pdf

Networking evening

I’m discussing with a number of network members, the possibility of the next session here at MMU on the evening of 26th May, being an opportunity to share ongoing work, frustration, needs and ideas. The simple idea being that a small number of artists/health practitioners get in touch with me if they’re interested and on the evening, they can share what it is they’d like to discuss…then we can pitch in with constructive criticism and support. This could be really helpful to all of us and I’m pleased to say that the artist Zoe Keenan is happy to share some of her work around dementia and young people who find themselves in the position of being a carer. Zoe has produced some really exciting work around this and would be happy to share it and get feedback.

Anyway, if you’re interested in sharing something, or if you just want to attend, please email me at artsforhealth@mmu.ac.uk

(Venue details will be emailed next week)

M A N I F E S T O update

Since the first session last September, just under 400 people around the region have contributed to the emerging m a n i f e s t o and over May and June we’ll be holding the last sessions of the first stage of conversations. In June, I’ll be working with colleagues from all over the North West and others from as far as Durham, Yorkshire, Australia, South Africa, Ireland and the USA, who’ll all be feeding into the discussion. The final event of 2011 will be at MMU in September…then, we go public! Don’t forget, we’ll be getting some high-profile input into the m a n i f e s t o from the art, media, health sectors too, but the core of this work is about our shared vision. On the 9th May I facilitated an event in Cumbria that was over-subscribed. As usual, if you wanted to contribute but weren’t able to attend, please get in touch via email. And for the 3 people who left comments in my ‘composting thoughts bag’ in Cumbria, a particularly big THANK YOU. Your comments will feed into the mix and I really liked the illustrations too.

In my last blog posting, I told you a little about the free event on June 30th that will see a host of international figures from the arts/health world, sharing some of their practice and engaging in conversation. I’ve been overwhelmed by the response and it looks like it will be fully booked well ahead of the event. I have to reiterate that I can’t guarantee anyone a place yet, but thanks for the emails. I will confirm places/agenda/venue/times at the beginning of June.

Towards a National Forum for Arts and Health

Many of you will know that I sit on a group that has been looking at the notion of a National Forum for Arts and Health, following the collapse of the NNAH in 2007. I’ve been working with colleagues around the country to explore ways forward, and the linked report has been made by the external consultants Globe to help inform this direction. I would be grateful for any thoughts on this linked document, which I will feed into the forum at our next meeting.

http://www.artsforhealth.org/resources/final_national_forum_report.pdf

Networking evening

I’m discussing with a number of network members, the possibility of the next session here at MMU on the evening of 26th May, being an opportunity to share ongoing work, frustration, needs and ideas. The simple idea being that a small number of artists/health practitioners get in touch with me if they’re interested and on the evening, they can share what it is they’d like to discuss…then we can pitch in with constructive criticism and support. This could be really helpful to all of us and I’m pleased to say that the artist Zoe Keenan is happy to share some of her work around dementia and young people who find themselves in the position of being a carer. Zoe has produced some really exciting work around this and would be happy to share it and get feedback.

Anyway, if you’re interested in sharing something, or if you just want to attend, please email me at artsforhealth@mmu.ac.uk

(Venue details will be emailed next week)

M A N I F E S T O update

Since the first session last September, just under 400 people around the region have contributed to the emerging m a n i f e s t o and over May and June we’ll be holding the last sessions of the first stage of conversations. In June, I’ll be working with colleagues from all over the North West and others from as far as Durham, Yorkshire, Australia, South Africa, Ireland and the USA, who’ll all be feeding into the discussion. The final event of 2011 will be at MMU in September…then, we go public! Don’t forget, we’ll be getting some high-profile input into the m a n i f e s t o from the art, media, health sectors too, but the core of this work is about our shared vision. On the 9th May I facilitated an event in Cumbria that was over-subscribed. As usual, if you wanted to contribute but weren’t able to attend, please get in touch via email. And for the 3 people who left comments in my ‘composting thoughts bag’ in Cumbria, a particularly big THANK YOU. Your comments will feed into the mix and I really liked the illustrations too.

Monday, May 9, 2011

Looking for a good orthodontist? My recommendation is Dr. Meat

The figure below is one of many in Weston Price’s outstanding book Nutrition and Physical Degeneration showing evidence of teeth crowding among children whose parents moved from a traditional diet of minimally processed foods to a Westernized diet.

Tooth crowding and other forms of malocclusion are widespread and on the rise in populations that have adopted Westernized diets (most of us). Some blame it on dental caries, particularly in early childhood; dental caries are also a hallmark of Westernized diets. Varrela (2007), however, in a study of Finnish skulls from the 15th and 16th centuries found evidence of dental caries, but not of malocclusion, which Varrela reported as fairly high in modern Finns.

Why does malocclusion occur at all in the context of Westernized diets? Lombardi (1982) put forth an evolutionary hypothesis:

So what is one to do? Apparently getting babies to eat meat is not a bad idea. They may well just chew on it for a while and spit it out. The likelihood of meat inducing dental caries is very low, as most low carbers can attest. (In fact, low carbers who eat mostly meat often see dental caries heal.)

Concerned about the baby choking on meat? At the time of this writing a Google search yielded this: No results found for “baby choked on meat”. Conversely, Google returned 219 hits for “baby choked on milk”.

What if you have a child with crowded teeth as a preteen or teen? Too late? Should you get him or her to use “cute” braces? Our daughter had crowded teeth a few years ago, as a preteen. It overlapped with the period of my transformation, which meant that she started having a lot more natural foods to eat. There were more of those around, some of which require serious chewing, and less industrialized soft foods. Those natural foods included hard-to-chew beef cuts, served multiple times a week.

We noticed improvement right away, and in a few years the crowding disappeared. Now she has the kind of smile that could land her a job as a toothpaste model:

The key seems to be to start early, in developmental years. If you are an adult with crowded teeth, malocclusion may not be solved by either tough foods or braces. With braces, you may even end up with other problems (see this).

Tooth crowding and other forms of malocclusion are widespread and on the rise in populations that have adopted Westernized diets (most of us). Some blame it on dental caries, particularly in early childhood; dental caries are also a hallmark of Westernized diets. Varrela (2007), however, in a study of Finnish skulls from the 15th and 16th centuries found evidence of dental caries, but not of malocclusion, which Varrela reported as fairly high in modern Finns.

Why does malocclusion occur at all in the context of Westernized diets? Lombardi (1982) put forth an evolutionary hypothesis:

“In modern man there is little attrition of the teeth because of a soft, processed diet; this can result in dental crowding and impaction of the third molars. It is postulated that the tooth-jaw size discrepancy apparent in modern man as dental crowding is, in primitive man, a crucial biologic adaptation imposed by the selection pressures of a demanding diet that maintains sufficient chewing surface area for long-term survival. Selection pressures for teeth large enough to withstand a rigorous diet have been relaxed only recently in advanced populations, and the slow pace of evolutionary change has not yet brought the teeth and jaws into harmonious relationship.”

So what is one to do? Apparently getting babies to eat meat is not a bad idea. They may well just chew on it for a while and spit it out. The likelihood of meat inducing dental caries is very low, as most low carbers can attest. (In fact, low carbers who eat mostly meat often see dental caries heal.)

Concerned about the baby choking on meat? At the time of this writing a Google search yielded this: No results found for “baby choked on meat”. Conversely, Google returned 219 hits for “baby choked on milk”.

What if you have a child with crowded teeth as a preteen or teen? Too late? Should you get him or her to use “cute” braces? Our daughter had crowded teeth a few years ago, as a preteen. It overlapped with the period of my transformation, which meant that she started having a lot more natural foods to eat. There were more of those around, some of which require serious chewing, and less industrialized soft foods. Those natural foods included hard-to-chew beef cuts, served multiple times a week.

We noticed improvement right away, and in a few years the crowding disappeared. Now she has the kind of smile that could land her a job as a toothpaste model:

The key seems to be to start early, in developmental years. If you are an adult with crowded teeth, malocclusion may not be solved by either tough foods or braces. With braces, you may even end up with other problems (see this).

Sunday, May 8, 2011

Those daily extra cups of joe not linked to hypertension

An extra shot of espresso can surely help wake you up in the morning, but what does it mean for your blood pressure? It is well known that coffee's caffeine content can raise blood pressure temporarily, especially in people who have hypertension. Could habitually drinking high amounts have long-term effects on blood pressure too?

Java lovers will rejoice in a large study's findings that more cups daily isn't associated with increased risk of hypertension. The study, published in American Journal of Clinical Nutrition on March 30, was a systematic review and meta-analysis that examined six prospective cohort studies.

Two previous meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials found an association with slightly raised risk of hypertension. But these trials all lasted only 85 days or fewer days. In the new study, a total 172,567 participants and 37,135 incident cases of hypertension were followed over the course of six years.

Four of the six studies evaluated reported a nonlinear association between coffee consumption and hypertension, whereas two reported no statistically significant association. The pooled results revealed a relative risk of 1.09 (1.01; 1.18) from drinking 1 to 3 cups daily (a slightly elevated risk), 1.07 (0.96, 1.20) from drinking 3 to 5 cups daily, and 1.09 (0.96, 1.21) from drinking five or more cups daily.

The researchers suggested that the results of the study may be explained by coffee drinkers developing a tolerance to caffeine's acute effect on blood pressure, which is thought to be result of caffeine's binding to receptors that trigger a sympathetic nervous system response.

Additionally, another explanation may be that other ingredients in coffee like magnesium, potassium, or flavonoids could have a counterbalancing effect on blood pressure, which the researchers suggest may explain an inverse "J-shape" relationship between habitual coffee drinking and hypertension risk.

Since the way people metabolize caffeine in the liver can depend on genetics, the authors suggest more research is needed to determine coffee's effects on non-white populations.

Reference

Zhang Z, Hu G, Caballero B, Appel L, and Chen L. 2011. Habitual coffee consumption and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies1–3. Amer J Clin Nutr. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004044.

Java lovers will rejoice in a large study's findings that more cups daily isn't associated with increased risk of hypertension. The study, published in American Journal of Clinical Nutrition on March 30, was a systematic review and meta-analysis that examined six prospective cohort studies.

Two previous meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials found an association with slightly raised risk of hypertension. But these trials all lasted only 85 days or fewer days. In the new study, a total 172,567 participants and 37,135 incident cases of hypertension were followed over the course of six years.

Four of the six studies evaluated reported a nonlinear association between coffee consumption and hypertension, whereas two reported no statistically significant association. The pooled results revealed a relative risk of 1.09 (1.01; 1.18) from drinking 1 to 3 cups daily (a slightly elevated risk), 1.07 (0.96, 1.20) from drinking 3 to 5 cups daily, and 1.09 (0.96, 1.21) from drinking five or more cups daily.

The researchers suggested that the results of the study may be explained by coffee drinkers developing a tolerance to caffeine's acute effect on blood pressure, which is thought to be result of caffeine's binding to receptors that trigger a sympathetic nervous system response.

Additionally, another explanation may be that other ingredients in coffee like magnesium, potassium, or flavonoids could have a counterbalancing effect on blood pressure, which the researchers suggest may explain an inverse "J-shape" relationship between habitual coffee drinking and hypertension risk.

Since the way people metabolize caffeine in the liver can depend on genetics, the authors suggest more research is needed to determine coffee's effects on non-white populations.

Reference

Zhang Z, Hu G, Caballero B, Appel L, and Chen L. 2011. Habitual coffee consumption and risk of hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies1–3. Amer J Clin Nutr. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004044.

Diagnosing Darwin's multiple gastrointestinal diseases

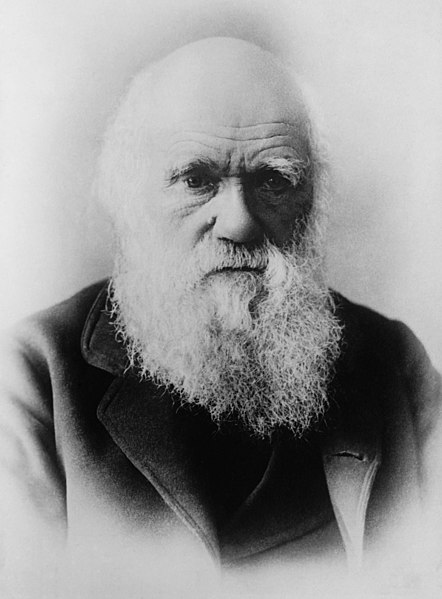

|

| Charles Darwin (Credit: Wikimedia) |

England's physicians of the time could not properly diagnose the syndrome of cyclic vomiting, although they tried by suggesting its etiology was anything to do with allergies, gout, and mental overwork. But what of an assessment of Darwin's symptoms by modern physicians of today?

On Friday, May 6, modern physicians gathered to discuss Darwin's lifelong illness at the 18th Historical Clinicopathological Conference sponsored by University of Maryland Health Care System. The conference previously has examined and provided modern medical diagnoses of other prominent historical figures such as Abraham Lincoln and Edgar Allan Poe. The scientists chose Darwin for this year's conference to commemorate the naturalist's 200th birthday.

At the conference, the medical researchers determined that the nature of Darwin's sickness may be explained by multiple gastrointestinal illnesses he might of contracted while traveling to remote areas of South America, the Pacific, Far East, and Africa. A transmission of parasites, for example, may have led to what would become chronic "Chagas disease" and "peptic ulcer disease," further explaining the onset of Darwin's cardiac symptoms and eventual heart disease.

Chagas disease is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, which transmitted to humans by blood-sucking insects known as reduviid bugs found throughout Mexico, Central and South America living in mud or adobe huts and feeding on humans. The insects probably bit at Darwin's body as he was sleeping, passing the parasites via their feces, then entered his body through eyes, mouth or an open wound facilitated by the unsuspecting victim scratched himself. Chagas disease can have an acute phase in which symptoms of nausea and vomiting combined with headaches could last for weeks or months, then if untreated can lead to a chronic phase.

“Chagas would describe the heart disease, cardiac failure or ‘degeneration of the heart’ — the term used in Darwin’s time to mean heart disease — that he suffered from later in life and that eventually caused his death,” said Sidney Cohen, M.D., who led the diagnosis and was quoted in a press release. Dr. Cohen is a professor of medicine and director of research of Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Peptic ulcer disease is caused by infection with the common bacteria, Helicobacter pylori. Darwin probably contracted the bacteria from contact with saliva or feces of another human or from drinking untreated water. Then, the bacteria making itself at home in Darwin's stomach by creating a low-acid "buffer zone," could also explain symptoms of severe abdominal pain, bloating, frequent burping, nausea and vomiting.

“H. pylori and Chagas disease can be contracted in the same areas of the world and often occur together,” Cohen said.

Why was it supposed that Darwin suffered from two or more illnesses? According to Cohen, “Darwin’s lifelong history does not fit neatly into a single disorder based historically only upon symptom assessment. I make the argument that Darwin had multiple illnesses in his lifetime.”

Medical History

The clinicians evaluated Darwin's medical history, which included a look at his excellent health as a child (with an occasional upset stomach; happens to us all) followed by his leaving England at age 22 on a five-year voyage on the Beagle. During his travels, Darwin suffered from frequent seasickness, fevers, two instances of food poisoning, intermittent boils, an inflamed knee and arm, and "Chilean fever."

A year after his arrival back in England, at age 27, began what would become a lifelong illness. He complained of violent cardiac palpitations and headaches at 29, which returned once at 51 and just before he died. In his 30s he had a few episodes of fingertip numbness, buzzing in his head, seeing stars, involuntary hand twitching. In his 50s, he complained of weakness and intermittent rheumatism. At age 57, he also was bruised badly after his horse fell and rolled on him.

A look at his diet and lifestyle suggests Darwin's behavior was not unlike those of most other scientists of the day. It included smoking the occasional cigarette and cigar, moderate drinking of brandy, wine and port, and walking as his only exercise.

His family history included his father, who was morbidly obese, and suffered from gout. He had an older brother who struggled with depression and died at age 77 of an unknown cause and three sisters who all died of unknown causes.

In the last decade before his death, Darwin's health seemed to improve as his chronic cyclic nausea and vomiting eased up. But his memory began to decline and at age 72, he suffered a sudden "fit of dazzling" and irregular pulse while hiking. He developed a cough alleviated by quinine. Later one evening while eating dinner, he was seized by dizziness and he fainted while trying to reach the couch. He regained consciousness, drank brandy and seemed to recover, but then started to vomit relentlessly until what lasted until the next day when he lost consciousness again and died.

At the time of his death at age 73, he was diagnosed with "angina attacks with heart failure and degeneration of the heart and greater blood vessels."

Friday, May 6, 2011

Getting off the death chair

|

| My stand-up desk |

Physical activity is strongly linked to brain performance. The exercise boosts blood flow in the brain and improves our memory and cognitive function. Exercise acts like a trigger for the brain saying, "It's time to be alert, find food, survive." Exercise may even fuel brain power by increasing neurogenesis and also guard against the harmful effects of stress.

Yet now we sit, and sit, and sit. Until the sitting kills us.

This article in the New York Times magazine gives a pretty good description of just what really happens when you sit in that death chair with quotes from Marc Hamilton, an inactivity researcher at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center:

This is your body on chairs: Electrical activity in the muscles drops — “the muscles go as silent as those of a dead horse,” Hamilton says — leading to a cascade of harmful metabolic effects. Your calorie-burning rate immediately plunges to about one per minute, a third of what it would be if you got up and walked. Insulin effectiveness drops within a single day, and the risk of developing Type 2 diabetes rises. So does the risk of being obese. The enzymes responsible for breaking down lipids and triglycerides — for “vacuuming up fat out of the bloodstream,” as Hamilton puts it — plunge, which in turn causes the levels of good (HDL) cholesterol to fall.Isn't that enough to scare the "sit" out of you? If not, this infographic will do the trick.

I've decided to stand up. So, as seen in the photo above, I took a bunch of my thickest textbooks and used them as supports to raise my monitors to eye level when standing.

With luck -- probably because the Human Resources department was mortified by how ugly desk my desk was -- I later got mechanical arms that can move the monitors up and down as I like. It's much better than the books. And I think pretty much everyone should now have a desk like mine.

Because since the time that I started using my new stand-up desk, my neck and back pain has gone away almost entirely.

Eventually, I expect, I'll be persuaded to try a treadmill desk.

Labels:

Stand-up desk

Safe weight loss for seniors through diet and exercise

In the United States, the number of obese older adults has reached disturbing heights—now affecting approximately 20 percent of those ages 65 and older—and is only expected to rise as more Baby Boomers become senior citizens.

Weight loss through calories reduction or exercise are generally good for most people as an intervention in obesity, although the appropriateness of these methods has historically been a matter of controversy in older, obese adults.

A major concern with weight loss is the accompanying loss of lean tissue, which can accelerate existing sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle and strength), and result in reduction of bone mineral density that could worsen frailty. This could lead to greater risk of bone fractures and broken hips. Studies have yet to provide sufficient evidence, one way or another, as to whether or not weight loss provides a true enhancement to quality of life.

In a one-year, randomized, controlled trial, researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis evaluated independent and combined effects of weight loss and exercise in nearly 100 obese older adults with an average age of 70.

The study, published their findings in the March issue of New England Journal of Medicine, randomized subjects into one of four groups:

1. Control group – participants of which did not receive any advice to change diet or activity.

2. Diet group – prescribed a diet with a deficit of 500 to 750 Calories per day and containing 1 gram of high-quality protein per kilogram of body weight per day

2. Diet group – prescribed a diet with a deficit of 500 to 750 Calories per day and containing 1 gram of high-quality protein per kilogram of body weight per day

3. Exercise group – prescribed a diet to maintain weight while participating in three group exercise trainings weekly, which included 90 minutes of aerobic exercises, resistance trainings, and flexibility and balance exercises.

4. Diet-exercise group – prescribed a combination of the weight management instructions and exercise trainings as described in 1 and 2.

To "even the playing field" and reduce confounding variables of vitamin D and calcium status, the researchers gave all participants supplements: approximately 1500 milligrams of calcium and 1000 IU of vitamin D per day.

Results from this carefully designed study show the "diet-exercise group" preserved more lean muscle and bone density when compared to the other groups. They gained significantly better physical function and were less frail than other groups and outperformed other groups in all measured parameters: Physical Performance Test (PPT), peak oxygen consumption (VO2pseak), and Functional Status Questionnaire (FSQ) (see graphs).

"Weight loss combined with regular exercise may be beneficial in helping obese older adults maintain their functional independence," the authors concluded.

Generally, most older, obese adults are able to safely engage in regular physical activity; however, a medical professional can determine which exercises are appropriate for an individual's specific needs. Because fitness levels vary, it's important to consult a physician prior to beginning any exercise program. Certain medical conditions, as well as medications, can also affect a person’s tolerance for exercise.

Engaging in a variety of exercises, such as aerobic exercises, resistance training, and flexibility exercises, can lead to optimal health benefits. Each is essential for healthy aging.

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic exercise of moderate intensity, 30 minutes a day, five times per week is currently recommended for adults ages 65 and older, according to the guidelines presented by the American College Sports of Medicine (ACSM). Those who are not used to exercising can start out with a shorter duration at a lower intensity and work their way up to the recommendations.

Aerobic exercise can lead to improved cardiovascular function, better quality of sleep, improved mental health, weight loss and enhanced immune function. Suggested aerobic activities for older adults include low-impact exercises such as walking, biking, low-impact aerobics, and water activities such as swimming or water aerobics.

Resistance Training

Resistance training is essential to preserve lean muscle and bone density or even reverse previous losses. In addition to improving physical function, resistance-based exercises can also reduce risk of some medical conditions like diabetes and hypertension.

Older, obese adults should perform resistance-training exercises two times weekly. The trainings should consist of 8 to 10 different strength exercises with 8 to 12 repetitions each. Again, it's best to start out slow, with lighter weights and fewer repetitions.

There are many different types of strength training exercises and a variety of equipment that can be used, including: weight-training machines, dumbbells, resistance bands, medicine balls, weighted bars, resistance of water or even one’s own body weight.

For optimal benefits, it is best to work muscles to the point of fatigue, without overstraining, while taking enough time between workouts to allow the muscles to rest and recover.

Flexibility Exercises

Flexibility and balance are also factors important to health that decrease with age. Leading a sedentary lifestyle can cause connective tissues to weaken and joints to stiffen. Ultimately, the lack of activity affects a person's range of motion, balance and posture.

Performing stretching exercises regularly can help improve flexibility and increase freedom of movement. Every workout should begin and end with proper stretching exercises to help warm up and soothe the muscles. Stretching, along with strength exercises, can also improve balance, which can help reduce the risk of falling – particularly important for elderly individuals.

Final Word

It's never too late to begin a weight-control and exercise program. Along with a healthy diet, engaging in individually-appropriate physical activity—aerobics, resistance training, and flexibility exercises—can provide older adults with improved physical function and a variety of health benefits.

Reference

Villareal DT, Chode S, Parimi N et al. Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1218-29.

Weight loss through calories reduction or exercise are generally good for most people as an intervention in obesity, although the appropriateness of these methods has historically been a matter of controversy in older, obese adults.

A major concern with weight loss is the accompanying loss of lean tissue, which can accelerate existing sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle and strength), and result in reduction of bone mineral density that could worsen frailty. This could lead to greater risk of bone fractures and broken hips. Studies have yet to provide sufficient evidence, one way or another, as to whether or not weight loss provides a true enhancement to quality of life.

In a one-year, randomized, controlled trial, researchers from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis evaluated independent and combined effects of weight loss and exercise in nearly 100 obese older adults with an average age of 70.

The study, published their findings in the March issue of New England Journal of Medicine, randomized subjects into one of four groups:

1. Control group – participants of which did not receive any advice to change diet or activity.

2. Diet group – prescribed a diet with a deficit of 500 to 750 Calories per day and containing 1 gram of high-quality protein per kilogram of body weight per day

2. Diet group – prescribed a diet with a deficit of 500 to 750 Calories per day and containing 1 gram of high-quality protein per kilogram of body weight per day 3. Exercise group – prescribed a diet to maintain weight while participating in three group exercise trainings weekly, which included 90 minutes of aerobic exercises, resistance trainings, and flexibility and balance exercises.

4. Diet-exercise group – prescribed a combination of the weight management instructions and exercise trainings as described in 1 and 2.

To "even the playing field" and reduce confounding variables of vitamin D and calcium status, the researchers gave all participants supplements: approximately 1500 milligrams of calcium and 1000 IU of vitamin D per day.

Results from this carefully designed study show the "diet-exercise group" preserved more lean muscle and bone density when compared to the other groups. They gained significantly better physical function and were less frail than other groups and outperformed other groups in all measured parameters: Physical Performance Test (PPT), peak oxygen consumption (VO2pseak), and Functional Status Questionnaire (FSQ) (see graphs).

"Weight loss combined with regular exercise may be beneficial in helping obese older adults maintain their functional independence," the authors concluded.

Generally, most older, obese adults are able to safely engage in regular physical activity; however, a medical professional can determine which exercises are appropriate for an individual's specific needs. Because fitness levels vary, it's important to consult a physician prior to beginning any exercise program. Certain medical conditions, as well as medications, can also affect a person’s tolerance for exercise.

Engaging in a variety of exercises, such as aerobic exercises, resistance training, and flexibility exercises, can lead to optimal health benefits. Each is essential for healthy aging.

Aerobic Exercise

Aerobic exercise of moderate intensity, 30 minutes a day, five times per week is currently recommended for adults ages 65 and older, according to the guidelines presented by the American College Sports of Medicine (ACSM). Those who are not used to exercising can start out with a shorter duration at a lower intensity and work their way up to the recommendations.

Aerobic exercise can lead to improved cardiovascular function, better quality of sleep, improved mental health, weight loss and enhanced immune function. Suggested aerobic activities for older adults include low-impact exercises such as walking, biking, low-impact aerobics, and water activities such as swimming or water aerobics.

Resistance Training

Resistance training is essential to preserve lean muscle and bone density or even reverse previous losses. In addition to improving physical function, resistance-based exercises can also reduce risk of some medical conditions like diabetes and hypertension.

Older, obese adults should perform resistance-training exercises two times weekly. The trainings should consist of 8 to 10 different strength exercises with 8 to 12 repetitions each. Again, it's best to start out slow, with lighter weights and fewer repetitions.

There are many different types of strength training exercises and a variety of equipment that can be used, including: weight-training machines, dumbbells, resistance bands, medicine balls, weighted bars, resistance of water or even one’s own body weight.

For optimal benefits, it is best to work muscles to the point of fatigue, without overstraining, while taking enough time between workouts to allow the muscles to rest and recover.

Flexibility Exercises

Flexibility and balance are also factors important to health that decrease with age. Leading a sedentary lifestyle can cause connective tissues to weaken and joints to stiffen. Ultimately, the lack of activity affects a person's range of motion, balance and posture.

Performing stretching exercises regularly can help improve flexibility and increase freedom of movement. Every workout should begin and end with proper stretching exercises to help warm up and soothe the muscles. Stretching, along with strength exercises, can also improve balance, which can help reduce the risk of falling – particularly important for elderly individuals.

Final Word

It's never too late to begin a weight-control and exercise program. Along with a healthy diet, engaging in individually-appropriate physical activity—aerobics, resistance training, and flexibility exercises—can provide older adults with improved physical function and a variety of health benefits.

Reference

Villareal DT, Chode S, Parimi N et al. Weight loss, exercise, or both and physical function in obese older adults. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1218-29.

Tuesday, May 3, 2011

Printing organs for transplants

Advances in medicine are allowing us to live longer than ever, but with our older age comes a greater risk that our organs will fail us. In fact, the shortage of organs available for transplant increases by the day, according to Anthony Atala who spoke at TEDMED.

In his talk, posted in March, Atala presents developments in regenerative medicine including new devices that use the same technology of scanners, fax, copy machines and printers. Instead of using ink in their cartridges, they simply use cells.

On stage, Atala shows us how one of these devices works, actually printing a kidney in as little as seven hours. It's mind bending.

I feel as though I'd like to show this video to every person I know. This is our future medicine. This technology will no doubt keep us living longer than ever. One day, like salamanders, we will be growing our own organs whenever needed -- kidneys, livers, lungs, etc.

Can you even imagine? Eat and drink whatever you like, ruin your liver and kidneys, then have new ones printed in all but a few hours, and you're as good as new?

It's almost sickening.

Labels:

Future Health

Arts and Health: Head to Head

|

| SIYAZAMA PROJECT |

These include, amongst others Executive Director of Arts and Health Australia, Margret Meagher; Murdoch University's Dr Peter Wright; Executive Director of DADAA, David Doyle, Durban University of Technolgy's Professor Kate Wells and the Centre for Medical Humanities', Mike White.

This event will offer participants the chance to hear about some global exemplars in arts and community health and research, and take part in a discussion and networking session.

This event is free and places are going to be limited. It is likely that it will take place between 3:00 and 6:00.

|

| Tim Maley Exhibition DADAA |

Confirmation of a place will be provided in early June, as will fine details of the event including agenda, time and venue.

News that "Nutcracker Man didn't eat nuts" isn't exactly news

|

| Photosimulation montages of "Nutcracker Man's" dental microwear. Reference: Ungar et al. PLoS One 2008. |

But, it turns out, the hominin species who in evolutionary terms has been likened to our great uncle was more likely to have eaten soft fruits, leaves and grass, according to carbon stable isotope data just published in PNAS by Thure Cerling and his team from University of Utah.

See more about Cerling's paper on John Hawks's blog.

A big deal has been made of this new paper and rightly so, but reporters should also note that the findings are a confirmation of what was already supposed based on dental microwear (shown above) almost exactly three years ago.

On 30 April 2008, Peter Ungar and colleagues at University of Arkansas also told us Nutcracker Man didn't eat nuts in a study in PLoS One (and featured by @9brandon in Wired Science here) citing wear and tear on the hominin's teeth that looked nothing like that of what would've been produced by hard foods.

Labels:

evolution

Monday, May 2, 2011

Michael Ruse on "Origins of Human Evolution"

|

| Michael Ruse |

Why were the great Greek philosophers (including Plato and Aristotle) firmly set against the idea of natural origins? Why were they so adamant that natural origins were impossible? According to Michael Ruse, a philosopher of biology at Florida State University, the reason is the problem of "final causes."

Aristotle, for example, "could not see how something like this could come about through blind law," said Ruse in a lecture given at Arizona State University’s Origins Project Science and Culture Festival on April 7, 2011.

This is why, for good scientific reason, said Ruse, they turned their back and rejected the idea of natural origins.

What was the big move? Robert Boyle particularly put his finger on it, said Ruse, we’ve changed the thinking of the world as an organism, to the world as a clock. This was a new metaphor for the world—the world is at some level a machine.

Going into the 18th century, the ideology of progress began to emerge—people began to thinking about social progress in biological terms. This is how the notion of evolution became set into the culture.

In the time of Erasmus Darwin, Charles's father, he became an evolutionist (what he called "transmutation") and was a strong promoter of social progress. He wrote that progress evolution, "is analogous to the improving excellence observable in every part of the creation… such as the progressive increase of the wisdom and happiness of its inhabitants."

Concurrently, others of the same time period loathed the ideology of evolution and social progress. Religion may have been part of it. What they really loathed is the idea of progressiveness, the change it brings.

Charles Darwin changed things dramatically, Ruse said. He established the fact of evolution. He made evolution a science. In his Origins of Species, he doesn’t talk about humans very much, but everybody knew this was the big issue.

"He wants to get the basic theory on the table," Ruse said, yet Darwin knew very well what it implied for humankind. There was no question that Darwin believed that humans emerged by the same natural mechanism as other species.