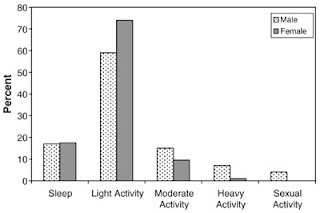

The figure below (click to enlarge) is from the outstanding book Physiology of sport and exercise, by Jack H. Wilmore, David L. Costill, and W. Larry Kenney. If you are serious about endurance or resistance exercise, or want to have a deeper understanding of exercise physiology beyond what one can get in popular exercise books, this book should be in your personal and/or institutional library. It is one of the most comprehensive textbooks on exercise physiology around. The full reference to the book is at the end of this post.

The hormonal and free fatty acid responses shown on the two graphs are to relatively intense exercise combining aerobic and anaerobic components. Something like competitive cross-country running in an area with hills would lead to that type of response. As you can see, cortisol spikes at the beginning, combining forces with adrenaline and noradrenaline (a.k.a. epinephrine and norepinephrine) to quickly increase circulating free fatty acid levels. Then free fatty acid levels are maintained elevated by adrenaline, noradrenaline, and growth hormone. As you can see from the graphs, free fatty acid levels are initially pulled up by cortisol, and then are very strongly correlated with adrenaline and noradrenaline. Those free fatty acids feed muscle, and also lead to the production of ketones, which provide extra fuel for muscle tissue.

Growth hormone stays flat for about 40 minutes, after which it goes up steeply. At around the 90-minute mark, it reaches a level that is quite high; 300 percent higher than it was prior to the exercise session. Natural elevation of circulating growth hormone through intense exercise, intermittent fasting, and restful sleep, leads to a number of health benefits. It helps burn abdominal fat, often hours after the exercise session, and helps builds muscle (in conjunction with other hormones, such as testosterone). It appears to increase insulin sensitivity in the long run. Maybe natural elevation of circulating growth hormone is one of the “secrets” of people like Bob Delmonteque, who is probably the fittest octogenarian in the world today.

Aerobic activities normally do not elevate growth hormone levels, even though they are healthy, unless they lead to a significant degree of glycogen depletion. Glycogen is stored in the liver and muscle, with muscle storing about 5 times more than the liver (about 500 g in adults). Once those reserves go down significantly during exercise, it seems that growth hormone is recruited to ramp up fat catabolism and facilitate other metabolic processes. Walking for an hour, even if briskly, is good for fat burning, but generates only a small growth hormone elevation. Including a few all-out sprints into that walk can help significantly increase growth hormone secretion.

Having said that, it is not really clear whether growth hormone elevation is a response to glycogen depletion, or whether both happen together in response to another stimulus or related metabolic process. There are other factors that come into play as well. For example, circulating growth hormone increase is moderated by sex hormone (e.g., testosterone, estrogen) secretion, thus larger growth hormone increases in response to exercise are observed in older men than in older women. (Testosterone declines more slowly with age in men than estrogen does in women.) Also, growth hormone increase seems to be correlated with an increase in circulating ketones.

Heavy resistance exercise seems to lead to a higher growth hormone elevation per unit of time than endurance exercise. That is, an intense resistance training session lasting only 30 minutes can lead to an acute circulating growth hormone response, similar to that shown on the figure. The key seems to be reaching the point during the exercise where muscle glycogen stores are significantly depleted. Many people who weight-train achieve this regularly by combining a reasonable number of sets (e.g., 6-12), with repetitions in the muscle hypertrophy range (again, 6-12); and progressive overload, whereby resistance is increased incrementally every session.

Progressive overload is needed because glycogen reserves are themselves increased in response to training, so one has to increase resistance every session to keep up with those increases. This goes on only up to a point, a point of saturation, usually reached by elite athletes. Glycogen is the primary fuel for anaerobic exercise; fat is used as fuel in the recovery period between sets, and after the exercise is over. Glycogen is expended proportionally to the number of calories used in the anaerobic effort. Calories are expended proportionally to the total amount of weight moved around, and are also a function of the movements performed (moving a certain weight 1 feet spends less energy than moving it 3 feet). By the way, not much glycogen is depleted in a 30-minute session. The total caloric expenditure will probably be around 250 calories above the basal metabolic rate, which will require about 63 g of glycogen.

Many sensations are associated with reaching the glycogen depletion level required for an acute growth hormone response during heavy anaerobic exercise. Often light to severe nausea is experienced. Many people report a “funny” feeling, which is unmistakable to them, but very difficult to describe. In some people the “funny” feeling is followed, after even more exertion, by a progressively strong sensation of “pins and needles”, which, unlike that associated with a heart attack, comes slowly and also goes away slowly with rest. Some people feel lightheaded as well.

It seems that the optimal point is reached immediately before the above sensations become bothersome; perhaps at the onset of the “funny” feeling. My personal impression is that the level at which one experiences the “pins and needles” sensation should be avoided, because that is a point where your body is about to “force” you to stop exercising. (Note: I am not a bodybuilder; see “Interesting links” for more extensive resources on the subject.) Besides, go to that point or beyond and significant muscle catabolism may occur, because the body prioritizes glycogen reserves over muscle protein. It will break that protein down to produce glucose via gluconeogenesis to feed muscle glycogenesis.

That the body prioritizes muscle glycogen reserves over muscle protein is surprising to many, but makes evolutionary sense. In our evolutionary past, there were no selection pressures on humans to win bodybuilding tournaments. For our hominid ancestors, it was more important to have the glycogen tank at least half-full than to have some extra muscle protein. Without glycogen, the violent muscle contractions needed for a “fight or flight” response to an animal attack simply cannot happen. And large predators (e.g., a bear) would not feel intimated by big human muscles alone; it would be the human’s response using those muscles that would result in survival or death.

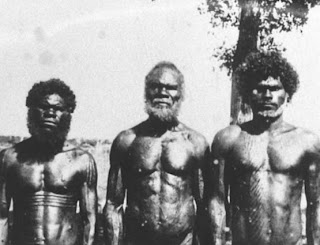

Overall, selection pressures probably favored functional strength combined with endurance, leading to body types similar to those of the hunter-gatherers shown on this post.

Even though the growth hormone response to exercise can be steep, the highest natural growth hormone spike seems to be the one that occurs at night, during deep sleep.

Exercising hard pays off, but only if one sleeps well.

Reference:

Wilmore, J.H., Costill, D.L., & Kenney, W.L. (2007). Physiology of sport and exercise. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Sunday, May 30, 2010

Friday, May 28, 2010

62-yr-old Woman with Hypertention, Ventricular Hypertrophy and Congestive Heart Failure

One of the considerations with congestive heart failure is the need for fluid restriction and the patient will need to work her doctor to be able understand how much she should be getting daily.

Sodium restriction is important for bringing down the blood pressure. In the case of this woman, I would employ a DASH diet to bring down her blood pressure with emphasis on plenty of fruits and vegetables as well as dairy products such as yogurt to obtain regular amounts of calcium.

Since being overweight contributes to higher blood pressure, if she is overweight, then the DASH diet should be combined with a weight loss program by restriction of calories.

Regular aerobic exercise can also support healthy blood pressure levels. I'd recommend about 30 minutes three times weekly.

Because of her condition, I'd also recommend supplementation with CoQ10 to support the function of the heart. If she has a low vitamin D status, which is associated with higher blood pressure, then I'd also recommend a vitamin D supplement.

Sodium restriction is important for bringing down the blood pressure. In the case of this woman, I would employ a DASH diet to bring down her blood pressure with emphasis on plenty of fruits and vegetables as well as dairy products such as yogurt to obtain regular amounts of calcium.

Since being overweight contributes to higher blood pressure, if she is overweight, then the DASH diet should be combined with a weight loss program by restriction of calories.

Regular aerobic exercise can also support healthy blood pressure levels. I'd recommend about 30 minutes three times weekly.

Because of her condition, I'd also recommend supplementation with CoQ10 to support the function of the heart. If she has a low vitamin D status, which is associated with higher blood pressure, then I'd also recommend a vitamin D supplement.

Labels:

nutr therap

Thursday, May 27, 2010

Postprandial glucose levels, HbA1c, and arterial stiffness: Compared to glucose, lipids are not even on the radar screen

Postprandial glucose levels are the levels of blood glucose after meals. In Western urban environments, the main contributors to elevated postprandial glucose are foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars. While postprandial glucose levels may vary somewhat erratically, they are particularly elevated in the morning after breakfast. The main reason for this is that breakfast, in Western urban environments, is typically very high in refined carbohydrates and sugars.

HbA1c, or glycated hemoglobin, is a measure of average blood glucose over a period of a few months. Blood glucose glycates (i.e., sticks to) hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells. Red blood cells are relatively long-lived, lasting approximately 3 months. Thus HbA1c (given in percentages) is a good indicator of average blood glucose levels, if you don’t suffer from anemia or a few other blood abnormalities.

Based on HbA1c, one can then estimate his or her average blood glucose level for the previous 3 months or so before the test, using one of the following equations, depending on whether the measurement is in mg/dl or mmol/l.

Average blood glucose (mg/dl) = 28.7 × HbA1c − 46.7

Average blood glucose (mmol/l) = 1.59 × HbA1c − 2.59

Elevated blood glucose levels cause damage in the body primarily through glycation, which leads to the formation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs). Given this, HbA1c can be seen as a proxy for the level of damage done by elevated blood glucose levels to various body tissues. This damage occurs over time; often after many years of high blood glucose levels. It includes kidney damage, neurological damage, cardiovascular damage, and damage to the retina.

Most regular blood exams focus on fasting blood glucose as a measure of glucose metabolism status. Many medical practitioners have as a target a fasting blood glucose level of 125 mg/dl (7 mmol/l) or less, and largely disregard postprandial glucose levels or HbA1c in their management of glucose metabolism. Leiter and colleagues (2005; full reference at the end of this post) showed that this focus on fasting blood glucose is a mistake. They are not alone; many others made this point, including some very knowledgeable bloggers who focus on diabetes (see “Interesting links” section of this blog). Leiter and colleagues (2005) also provided some interesting graphs and figures, including eye-opening correlations between various variables and arterial stiffness. The figure below (click to enlarge) shows the contribution of postprandial glucose to HbA1c.

Note that the lower the HbA1c is in the figure (horizontal axis), the higher is the postprandial glucose contribution to HbA1c. And, the lower the HbA1c, the closer the individuals are to what one could consider having a perfectly normal HbA1c level (around 5 percent). That is, only for individuals whose HbA1c levels are very high, fasting blood glucose levels are relatively reliable measures of the tissue damage done be elevated blood glucose levels.

The table below (click to enlarge) shows P values associated with the impact of various variables (listed on the leftmost column) on arterial stiffness. This measure, arterial stiffness, is strongly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Look at the middle column showing P values adjusted for age and height. The lower the P value, the more a variable affects arterial stiffness. The variable with the lowest P value by far is 2-hour postprandial blood glucose; the blood glucose levels measured 2 hours after meals.

Fasting glucose levels were reported to be statistically insignificant because of the P = 0.049, in terms of their effect on arterial stiffness, but this P value is actually significant, although barely, at the 0.05 level (95 percent confidence). Interestingly, the following measures are not even on the radar screen, as far as arterial stiffness is concerned: systolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting insulin levels.

What about the lipid hypothesis, and the “bad” LDL cholesterol!? This study is telling us that these are not very relevant for arterial stiffness when we control for the effect of blood glucose measures. Not even fasting insulin levels matters much! Wait, not even HDL!!! A high HDL has been definitely shown to be protective, but when we look at the relative magnitude of various effects, the story is a bit different. A high HDL’s protective effect exists, but it is dwarfed by the negative effect of high blood glucose levels, especially after meals, in the context of cardiovascular disease.

What all this points at is what we could call a postprandial glucose hypothesis: Lower your postprandial glucose levels, and live a longer, healthier life! And, by the way, if your postprandial glucose levels are under control, lipids do not matter much! Or maybe your lipids will fall into place, without any need for statin drugs, after your postprandial glucose levels are under control. One way or another, the outcome will be a positive one. That is what the data from this study is telling us.

How do you lower your postprandial glucose levels?

A good way to start is to remove foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars from your diet. Almost all of these are foods engineered by humans with the goal of being addictive; they usually come in boxes and brightly colored plastic wraps. They are not hard to miss. They are typically in the central aisles of supermarkets. The sooner you remove them from your diet, the better. The more completely you do this, the better.

Note that the evidence discussed in this post is in connection with blood glucose levels, not glucose metabolism per se. If you have impaired glucose metabolism (e.g., diabetes type 2), you can still avoid a lot of problems if you effectively control your blood glucose levels. You may have to be a bit more aggressive, adding low carbohydrate dieting (as in the Atkins or Optimal diets) to the removal of refined carbohydrates and sugars from your diet; the latter is in many ways similar to adopting a Paleolithic diet. You may have to take some drugs, such as Metformin (a.k.a. Glucophage). But you are certainly not doomed if you are diabetic.

Reference:

Leiter, L.A., Ceriello, A., Davidson, J.A., Hanefeld, M., Monnier, L., Owens, D.R., Tajima, N., & Tuomilehto, J. (2005). Postprandial glucose regulation: New data and new implications. Clinical Therapeutics, 27(2), S42-S56.

HbA1c, or glycated hemoglobin, is a measure of average blood glucose over a period of a few months. Blood glucose glycates (i.e., sticks to) hemoglobin, a protein found in red blood cells. Red blood cells are relatively long-lived, lasting approximately 3 months. Thus HbA1c (given in percentages) is a good indicator of average blood glucose levels, if you don’t suffer from anemia or a few other blood abnormalities.

Based on HbA1c, one can then estimate his or her average blood glucose level for the previous 3 months or so before the test, using one of the following equations, depending on whether the measurement is in mg/dl or mmol/l.

Average blood glucose (mg/dl) = 28.7 × HbA1c − 46.7

Average blood glucose (mmol/l) = 1.59 × HbA1c − 2.59

Elevated blood glucose levels cause damage in the body primarily through glycation, which leads to the formation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs). Given this, HbA1c can be seen as a proxy for the level of damage done by elevated blood glucose levels to various body tissues. This damage occurs over time; often after many years of high blood glucose levels. It includes kidney damage, neurological damage, cardiovascular damage, and damage to the retina.

Most regular blood exams focus on fasting blood glucose as a measure of glucose metabolism status. Many medical practitioners have as a target a fasting blood glucose level of 125 mg/dl (7 mmol/l) or less, and largely disregard postprandial glucose levels or HbA1c in their management of glucose metabolism. Leiter and colleagues (2005; full reference at the end of this post) showed that this focus on fasting blood glucose is a mistake. They are not alone; many others made this point, including some very knowledgeable bloggers who focus on diabetes (see “Interesting links” section of this blog). Leiter and colleagues (2005) also provided some interesting graphs and figures, including eye-opening correlations between various variables and arterial stiffness. The figure below (click to enlarge) shows the contribution of postprandial glucose to HbA1c.

Note that the lower the HbA1c is in the figure (horizontal axis), the higher is the postprandial glucose contribution to HbA1c. And, the lower the HbA1c, the closer the individuals are to what one could consider having a perfectly normal HbA1c level (around 5 percent). That is, only for individuals whose HbA1c levels are very high, fasting blood glucose levels are relatively reliable measures of the tissue damage done be elevated blood glucose levels.

The table below (click to enlarge) shows P values associated with the impact of various variables (listed on the leftmost column) on arterial stiffness. This measure, arterial stiffness, is strongly associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular events. Look at the middle column showing P values adjusted for age and height. The lower the P value, the more a variable affects arterial stiffness. The variable with the lowest P value by far is 2-hour postprandial blood glucose; the blood glucose levels measured 2 hours after meals.

Fasting glucose levels were reported to be statistically insignificant because of the P = 0.049, in terms of their effect on arterial stiffness, but this P value is actually significant, although barely, at the 0.05 level (95 percent confidence). Interestingly, the following measures are not even on the radar screen, as far as arterial stiffness is concerned: systolic blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and fasting insulin levels.

What about the lipid hypothesis, and the “bad” LDL cholesterol!? This study is telling us that these are not very relevant for arterial stiffness when we control for the effect of blood glucose measures. Not even fasting insulin levels matters much! Wait, not even HDL!!! A high HDL has been definitely shown to be protective, but when we look at the relative magnitude of various effects, the story is a bit different. A high HDL’s protective effect exists, but it is dwarfed by the negative effect of high blood glucose levels, especially after meals, in the context of cardiovascular disease.

What all this points at is what we could call a postprandial glucose hypothesis: Lower your postprandial glucose levels, and live a longer, healthier life! And, by the way, if your postprandial glucose levels are under control, lipids do not matter much! Or maybe your lipids will fall into place, without any need for statin drugs, after your postprandial glucose levels are under control. One way or another, the outcome will be a positive one. That is what the data from this study is telling us.

How do you lower your postprandial glucose levels?

A good way to start is to remove foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars from your diet. Almost all of these are foods engineered by humans with the goal of being addictive; they usually come in boxes and brightly colored plastic wraps. They are not hard to miss. They are typically in the central aisles of supermarkets. The sooner you remove them from your diet, the better. The more completely you do this, the better.

Note that the evidence discussed in this post is in connection with blood glucose levels, not glucose metabolism per se. If you have impaired glucose metabolism (e.g., diabetes type 2), you can still avoid a lot of problems if you effectively control your blood glucose levels. You may have to be a bit more aggressive, adding low carbohydrate dieting (as in the Atkins or Optimal diets) to the removal of refined carbohydrates and sugars from your diet; the latter is in many ways similar to adopting a Paleolithic diet. You may have to take some drugs, such as Metformin (a.k.a. Glucophage). But you are certainly not doomed if you are diabetic.

Reference:

Leiter, L.A., Ceriello, A., Davidson, J.A., Hanefeld, M., Monnier, L., Owens, D.R., Tajima, N., & Tuomilehto, J. (2005). Postprandial glucose regulation: New data and new implications. Clinical Therapeutics, 27(2), S42-S56.

Wednesday, May 26, 2010

Oven roasted meat: Pork tenderloin

This cut of pork is the equivalent in the pig of the filet mignon in cattle. It is just as soft, and lean too. A 100 g portion of roasted pork tenderloin will have about 22 g of protein, and 6 g of fat. Most of the fat will be monounsaturated and saturated, and some polyunsaturated. The latter will contain about 450 mg of omega-6 and 15 mg of omega-3 fats in it.

The saturated fat is good for you. The omega-6-to-omega-3 ratio is not a great one, but a 100 g portion will have a small absolute amount of omega-6 fats, which can be easily offset with some omega-3 from seafood or a small amount of fish oil. Pork tenderloin is easy to find in supermarkets, and is much less expensive than filet mignon, even though it is a relatively expensive cut of meat.

Below are the before and after photos of a roasted pork tenderloin we prepared and ate recently; a simple recipe follows the photos. This type of cooking leads to a Maillard reaction, which is clear from the browning of the meat and around it on the casserole. I am not too concerned; more about this after the recipe.

Below is the simple recipe. The roasted pork pieces come off easily after the roasting is done, and almost melt in the mouth!

- Make about 10 holes on 2 lbs of pork tenderloin, and add chopped garlic pieces into each of them.

- Pour about a cup of salsa evenly over the pork tenderloin pieces.

- Cover roasting container (casserole in photos) with aluminum foil to preserve moisture.

- Preheat over to 375 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Roast the pork tenderloin for about 3 hours.

Now back to the Maillard reaction. When it happens inside the body, it is a step in the formation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), which is not very good, as AGEs are believed to cause accelerated aging. However, the evidence that cooked meat is unhealthy, in the absence of leaky gut problems, is very slim. There are many hypothesized causes of the leaky gut syndrome, one of which is consumption of refined wheat products.

Our Paleolithic ancestors must have eaten charred meat on a regular basis, so it does not make much evolutionary sense to think that eating roasted meat leads to accelerated aging through the ingestion of AGEs. It is possible that eating charred meat caused health problems for our ancestors, and they threw their meat in the fire and then ate it charred anyway. Perhaps the health problems caused by charring were offset by the benefits of killing parasites living in meat with the heat of fire.

This is an open issue that needs much more research. Based on most of the research I have seen so far, eating roasted meat is not even in the same universe, in terms of the health problems that it can possibly generate, as is eating foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars (e.g., white bread, bagels, pasta, and non-diet sodas).

The saturated fat is good for you. The omega-6-to-omega-3 ratio is not a great one, but a 100 g portion will have a small absolute amount of omega-6 fats, which can be easily offset with some omega-3 from seafood or a small amount of fish oil. Pork tenderloin is easy to find in supermarkets, and is much less expensive than filet mignon, even though it is a relatively expensive cut of meat.

Below are the before and after photos of a roasted pork tenderloin we prepared and ate recently; a simple recipe follows the photos. This type of cooking leads to a Maillard reaction, which is clear from the browning of the meat and around it on the casserole. I am not too concerned; more about this after the recipe.

Below is the simple recipe. The roasted pork pieces come off easily after the roasting is done, and almost melt in the mouth!

- Make about 10 holes on 2 lbs of pork tenderloin, and add chopped garlic pieces into each of them.

- Pour about a cup of salsa evenly over the pork tenderloin pieces.

- Cover roasting container (casserole in photos) with aluminum foil to preserve moisture.

- Preheat over to 375 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Roast the pork tenderloin for about 3 hours.

Now back to the Maillard reaction. When it happens inside the body, it is a step in the formation of advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs), which is not very good, as AGEs are believed to cause accelerated aging. However, the evidence that cooked meat is unhealthy, in the absence of leaky gut problems, is very slim. There are many hypothesized causes of the leaky gut syndrome, one of which is consumption of refined wheat products.

Our Paleolithic ancestors must have eaten charred meat on a regular basis, so it does not make much evolutionary sense to think that eating roasted meat leads to accelerated aging through the ingestion of AGEs. It is possible that eating charred meat caused health problems for our ancestors, and they threw their meat in the fire and then ate it charred anyway. Perhaps the health problems caused by charring were offset by the benefits of killing parasites living in meat with the heat of fire.

This is an open issue that needs much more research. Based on most of the research I have seen so far, eating roasted meat is not even in the same universe, in terms of the health problems that it can possibly generate, as is eating foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars (e.g., white bread, bagels, pasta, and non-diet sodas).

Labels:

AGEs,

pork,

recipe,

roasting,

tenderloin

Monday, May 24, 2010

Intermittent fasting, engineered foods, leptin, and ghrelin

Engineered foods are designed by smart people, and the goal is not usually to make you healthy; the goal is to sell as many units as possible. Some engineered foods are “fortified” with the goal of making them as healthy as possible. The problem is that food engineers are competing with many millions of years of evolution, and evolution usually leads to very complex metabolic processes. Evolved mechanisms tend to be redundant, leading to the interaction of many particles, enzymes, hormones etc.

Natural foods are not designed to make you eat them nonstop. Animals do not want to be eaten (even these odd-looking birds below). Most plants do not “want” their various nutritious parts to be eaten. Fruits are exceptions, but plants do not want one single individual to eat all their fruits. That compromises seed dispersion. Multiple individual fruit eaters enhance seed dispersion. Plants "want" one individual animal to eat some of their fruits and then move on, so that other individuals can also eat.

It is safe to assume that doughnut manufacturers want one single individual to eat as many doughnuts as possible, and many individuals to want to do that. That takes some serious food engineering, and a lot of testing. Success will increase the manufacturers' revenues, the real bottom line for them. The medical establishment will then take care of those individuals, and prolong their miserable lives so that they can continue eating doughnuts for as long as possible. It is self-perpetuating system.

As mentioned in this previous post, to succeed in the practice of intermittent fasting, one has to stop worrying about food, and one good step in that direction is to avoid engineered foods. In this sense, intermittent fasting can be seen as a form of liberation. Doing something enjoyable and forgetting about food. Like children playing outdoors; they do not care as much about food as they do about play. Even sleeping will do; most people forget about eating when they are asleep.

Intermittent fasting as a religious and/or social activity, as in the Great Lent and Ramadan, also seems to work well. Any activity that brings people together with a common goal, especially if the goal is not to do something evil, has a lot of potential for success.

If you approach intermittent fasting as another thing to worry about, then it will be tough – one fast per week, on the same day of the week, from 7.33 pm of one day to 3.17 pm of the next day. I exaggerate a bit. Anyway, if you approach it as another obligation, another modern stressor, you will probably fail in the medium to long term. It is just commonsense. Maybe you will be able to do it for a while, but not for long enough to reap some serious benefits. A few fasts are not going to make you lose a lot of weight; the body will adapt in a compensatory way during the fast, slowing down your metabolism a bit and conserving calories. On top of that, you will feel very, very hungry. That will make you binge when you break your fast. Compensatory adaptation (a very general phenomenon) is something that our body is very good at, regardless of what we want it to do.

From a more pragmatic perspective, for most people it is easier to fast at night and in the morning. Eating a big meal right after you wake up is not a very natural activity; several hormones that promote body fat catabolism are often elevated in the morning, causing mild physiological insulin resistance.

If you have dinner at 7 pm, skip breakfast, and then have brunch the next day at 10 am, you will have fasted for 15 h. If you skip breakfast and brunch, and have lunch at noon the next day, you will have fasted for 17 h.

On the other hand, if you have breakfast at 8 am, skip lunch, and then have dinner at 6 pm, you will have fasted only for 10 h.

Leptin levels seem to go down significantly after 12 h of fasting, leading to increased body fat catabolism and leptin sensitivity. This is a good thing, since leptin resistance seems to frequently precede insulin resistance.

Many people think that skipping breakfast will make them fat, for various reasons, including that being what sumo wrestlers do to put on enormous amounts of body fat. Well, skipping breakfast probably will make people fat if, when they break the fast, they stuff themselves to the point of almost throwing up, combine plenty of easily digestible carbohydrates (e.g., multiple bowls of rice) with a lot of dietary fat, and then go to sleep. That is what sumo wrestlers normally do.

Eating fat is great, but not together with lots of easily digestible carbohydrates. Even eating a lot of fat by itself will make it difficult for you to shed enough fat to look like the hunter-gatherers in this post. But your body fat set point will be much lower if you eat a lot of fat by itself than if you eat a lot of fat with a lot of easily digestible carbohydrates.

Anyway, if people skip breakfast and eat what they normally eat at lunch, they will not gain more body fat than they would have if they had breakfast. If they do anything to boost their metabolism in the morning, they will most certainly lose body fat in a noticeable way over several weeks, as long as they have enough fat to lose. For example, they can add some light activity in the morning (such as walking), or have a metabolism-boosting drink (e.g., coffee, green tea), or both.

Our hunter-gatherer ancestors, living outdoors, probably spent most of their day performing light activities that involved little stress. Those activities increase metabolism and fat burning, while keeping stress hormone levels at low ranges. Hunger suppression was the result, making intermittent fasting fairly easy.

Again, intermittent fasting should be approached as a form of liberation. You are no longer a slave of food.

It helps staying away from engineered foods as much as possible, because, again, they are usually engineered with food addiction in mind. I am talking primarily about foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars. They come in boxes and plastic bags with labels describing calories and macronutrient composition, which are often wrong or misleading.

Let us say we could transport a group of archaic Homo sapiens to a modern city, and feed them white bread, bagels, doughnuts, potato chips industrially fried in vegetable oils, and the like. Would they say “Yuck, how can these people eat this?” No, they would not. It would be heaven for them; they would want nothing else for the rest of their gustatorily happy but health-wise miserable lives.

While practicing intermittent fasting, it is probably a good idea to have fixed meal times, and skipping them from time to time. The reason is the hunger hormone ghrelin, secreted by the stomach (mostly) and pancreas to stimulate hunger and possibly prepare the digestive tract for optimal or quasi-optimal absorption of food. Its secretion appears to follow the pattern of habitual meals adopted by a person.

References:

Elliott, W.H., & Elliott, D.C. (2009). Biochemistry and molecular biology. 4th Edition. New York: NY: Oxford University Press.

Fuhrman, J., & Barnard, N.D. (1995). Fasting and eating for health: A medical doctor's program for conquering disease. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Natural foods are not designed to make you eat them nonstop. Animals do not want to be eaten (even these odd-looking birds below). Most plants do not “want” their various nutritious parts to be eaten. Fruits are exceptions, but plants do not want one single individual to eat all their fruits. That compromises seed dispersion. Multiple individual fruit eaters enhance seed dispersion. Plants "want" one individual animal to eat some of their fruits and then move on, so that other individuals can also eat.

(Source: Teamsugar.com)

It is safe to assume that doughnut manufacturers want one single individual to eat as many doughnuts as possible, and many individuals to want to do that. That takes some serious food engineering, and a lot of testing. Success will increase the manufacturers' revenues, the real bottom line for them. The medical establishment will then take care of those individuals, and prolong their miserable lives so that they can continue eating doughnuts for as long as possible. It is self-perpetuating system.

As mentioned in this previous post, to succeed in the practice of intermittent fasting, one has to stop worrying about food, and one good step in that direction is to avoid engineered foods. In this sense, intermittent fasting can be seen as a form of liberation. Doing something enjoyable and forgetting about food. Like children playing outdoors; they do not care as much about food as they do about play. Even sleeping will do; most people forget about eating when they are asleep.

Intermittent fasting as a religious and/or social activity, as in the Great Lent and Ramadan, also seems to work well. Any activity that brings people together with a common goal, especially if the goal is not to do something evil, has a lot of potential for success.

If you approach intermittent fasting as another thing to worry about, then it will be tough – one fast per week, on the same day of the week, from 7.33 pm of one day to 3.17 pm of the next day. I exaggerate a bit. Anyway, if you approach it as another obligation, another modern stressor, you will probably fail in the medium to long term. It is just commonsense. Maybe you will be able to do it for a while, but not for long enough to reap some serious benefits. A few fasts are not going to make you lose a lot of weight; the body will adapt in a compensatory way during the fast, slowing down your metabolism a bit and conserving calories. On top of that, you will feel very, very hungry. That will make you binge when you break your fast. Compensatory adaptation (a very general phenomenon) is something that our body is very good at, regardless of what we want it to do.

From a more pragmatic perspective, for most people it is easier to fast at night and in the morning. Eating a big meal right after you wake up is not a very natural activity; several hormones that promote body fat catabolism are often elevated in the morning, causing mild physiological insulin resistance.

If you have dinner at 7 pm, skip breakfast, and then have brunch the next day at 10 am, you will have fasted for 15 h. If you skip breakfast and brunch, and have lunch at noon the next day, you will have fasted for 17 h.

On the other hand, if you have breakfast at 8 am, skip lunch, and then have dinner at 6 pm, you will have fasted only for 10 h.

Leptin levels seem to go down significantly after 12 h of fasting, leading to increased body fat catabolism and leptin sensitivity. This is a good thing, since leptin resistance seems to frequently precede insulin resistance.

Many people think that skipping breakfast will make them fat, for various reasons, including that being what sumo wrestlers do to put on enormous amounts of body fat. Well, skipping breakfast probably will make people fat if, when they break the fast, they stuff themselves to the point of almost throwing up, combine plenty of easily digestible carbohydrates (e.g., multiple bowls of rice) with a lot of dietary fat, and then go to sleep. That is what sumo wrestlers normally do.

Eating fat is great, but not together with lots of easily digestible carbohydrates. Even eating a lot of fat by itself will make it difficult for you to shed enough fat to look like the hunter-gatherers in this post. But your body fat set point will be much lower if you eat a lot of fat by itself than if you eat a lot of fat with a lot of easily digestible carbohydrates.

Anyway, if people skip breakfast and eat what they normally eat at lunch, they will not gain more body fat than they would have if they had breakfast. If they do anything to boost their metabolism in the morning, they will most certainly lose body fat in a noticeable way over several weeks, as long as they have enough fat to lose. For example, they can add some light activity in the morning (such as walking), or have a metabolism-boosting drink (e.g., coffee, green tea), or both.

Our hunter-gatherer ancestors, living outdoors, probably spent most of their day performing light activities that involved little stress. Those activities increase metabolism and fat burning, while keeping stress hormone levels at low ranges. Hunger suppression was the result, making intermittent fasting fairly easy.

Again, intermittent fasting should be approached as a form of liberation. You are no longer a slave of food.

It helps staying away from engineered foods as much as possible, because, again, they are usually engineered with food addiction in mind. I am talking primarily about foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars. They come in boxes and plastic bags with labels describing calories and macronutrient composition, which are often wrong or misleading.

Let us say we could transport a group of archaic Homo sapiens to a modern city, and feed them white bread, bagels, doughnuts, potato chips industrially fried in vegetable oils, and the like. Would they say “Yuck, how can these people eat this?” No, they would not. It would be heaven for them; they would want nothing else for the rest of their gustatorily happy but health-wise miserable lives.

While practicing intermittent fasting, it is probably a good idea to have fixed meal times, and skipping them from time to time. The reason is the hunger hormone ghrelin, secreted by the stomach (mostly) and pancreas to stimulate hunger and possibly prepare the digestive tract for optimal or quasi-optimal absorption of food. Its secretion appears to follow the pattern of habitual meals adopted by a person.

References:

Elliott, W.H., & Elliott, D.C. (2009). Biochemistry and molecular biology. 4th Edition. New York: NY: Oxford University Press.

Fuhrman, J., & Barnard, N.D. (1995). Fasting and eating for health: A medical doctor's program for conquering disease. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Sunday, May 23, 2010

Gallstone Development

Gallstones develop in the gallbladder, a small organ that stores and releases the bile made by the liver. Bile is a dark green fluid containing bile salts and cholesterol. The gallbladder releases bile into the small intestine to assist in digesting fats more efficiently. However, if the bile is contains high concentrations of cholesterol, then stones too difficult for the bile salts to dissolve may develop (1).

Losing weight too quickly or fasting can cause development of gallstones. The quick weight loss and fasting is thought to disturb the balance of bile salts and cholesterol (2;3).

The risk may increase if consuming a diet too low in fat. Avoiding fat reduces frequency of gallbladder emptying. This, in turn, may cause cholesterol to accumulate and lead to greater risk of forming stones (3;4).

References

1. Dowling RH. Review: pathogenesis of gallstones. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14 Suppl 2:39-47.

2. Wudel LJ, Jr., Wright JK, Debelak JP, Allos TM, Shyr Y, Chapman WC. Prevention of gallstone formation in morbidly obese patients undergoing rapid weight loss: results of a randomized controlled pilot study. J Surg Res 2002;102:50-6.

3. Festi D, Colecchia A, Orsini M et al. Gallbladder motility and gallstone formation in obese patients following very low calorie diets. Use it (fat) to lose it (well). Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998;22:592-600.

4. Vezina WC, Grace DM, Hutton LC et al. Similarity in gallstone formation from 900 kcal/day diets containing 16 g vs 30 g of daily fat: evidence that fat restriction is not the main culprit of cholelithiasis during rapid weight reduction. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:554-61.

Losing weight too quickly or fasting can cause development of gallstones. The quick weight loss and fasting is thought to disturb the balance of bile salts and cholesterol (2;3).

The risk may increase if consuming a diet too low in fat. Avoiding fat reduces frequency of gallbladder emptying. This, in turn, may cause cholesterol to accumulate and lead to greater risk of forming stones (3;4).

References

1. Dowling RH. Review: pathogenesis of gallstones. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2000;14 Suppl 2:39-47.

2. Wudel LJ, Jr., Wright JK, Debelak JP, Allos TM, Shyr Y, Chapman WC. Prevention of gallstone formation in morbidly obese patients undergoing rapid weight loss: results of a randomized controlled pilot study. J Surg Res 2002;102:50-6.

3. Festi D, Colecchia A, Orsini M et al. Gallbladder motility and gallstone formation in obese patients following very low calorie diets. Use it (fat) to lose it (well). Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1998;22:592-600.

4. Vezina WC, Grace DM, Hutton LC et al. Similarity in gallstone formation from 900 kcal/day diets containing 16 g vs 30 g of daily fat: evidence that fat restriction is not the main culprit of cholelithiasis during rapid weight reduction. Dig Dis Sci 1998;43:554-61.

Labels:

nutr therap

Homocysteinemia and Pernicious anemia

Pernicious anemia, a megaloblastic anemia caused by B12 deficiency, is associated with hyperhomocysteinemia. Because B12 is needed for methionine synthase to methylate homocysteine to methionine, a deficiency causes an accumulation of both homocysteine and methylmalonic acid (1). When both are elevated, marking the pernicious anemia, it can lead to progressive demyelination and neurological deterioration.

A folate deficiency may also result in megaloblastic anemia. If homocysteine is elevated but not methylmalonic acid, then the result is probably a folate deficiency. It is important for treatment to be correct. Large doses of folate can correct, or "mask," symptoms of pernicious anemia, which can result in irreversible neuropathy (2).

References

1. Devlin TM. Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations. Philadelphia: Wiley-Liss, 2002

2. Pagana, K.D., Pagana, T.J. Mostby's Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests, 3rd ed. Mosby Elsvier, 2006

A folate deficiency may also result in megaloblastic anemia. If homocysteine is elevated but not methylmalonic acid, then the result is probably a folate deficiency. It is important for treatment to be correct. Large doses of folate can correct, or "mask," symptoms of pernicious anemia, which can result in irreversible neuropathy (2).

References

1. Devlin TM. Textbook of Biochemistry with Clinical Correlations. Philadelphia: Wiley-Liss, 2002

2. Pagana, K.D., Pagana, T.J. Mostby's Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests, 3rd ed. Mosby Elsvier, 2006

Labels:

nutr therap

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Before Taking a Statin, Read This

I thought this was an interesting article from Businessweek a couple of years ago and was blown away by the numbers showing that few people actually receive any benefit from statins.

If you don't read it, then here are a few tidbits from the article that I thought would give it to you in a nutshell:

If you don't read it, then here are a few tidbits from the article that I thought would give it to you in a nutshell:

- ...for every 100 people in the trial, which lasted 3 1/3 years, three people on placebos and two people on Lipitor had heart attacks. The difference credited to the drug? One fewer heart attack per 100 people. So to spare one person a heart attack, 100 people had to take Lipitor for more than three years. The other 99 got no measurable benefit.

- ...an estimated 10% to 15% of statin users suffer side effects, including muscle pain, cognitive impairments, and sexual dysfunction

- "There's a tendency to assume drugs work really well, but people would be surprised by the actual magnitude of the benefits,"

- For anyone worried about heart disease, the first step should always be a better diet and increased physical activity. Do that, and "we would cut the number of people at risk so dramatically" that far fewer drugs would be needed...

- "The way our health-care system runs, it is not based on data, it is based on what makes money."

Friday, May 21, 2010

Predicting a Heart Attack with CRP

Currently, the existing biomarkers for a cardiac event include B-type natriuretic peptide, tro-ponins and C-reactive protein. C-reactive protein is an acute-phase protein released in response to inflammation.

Recently, the development of a high-sensitivity assay for CRP (hs-CRP) has been made available. The assay works because it can accurately reflect even low levels of CRP. There have been quite a few prospective studies that have shown that an assay of a baseline CRP can be used as a marker for cardiovascular events.

When patients have a test that shows elevated levels, it is even a better marker than LDL cholesterol for predicting events such as myocardial infarction. An elevated test, however, can also mean hypertension, metabolic syndrome or diabetes, or a chronic infection.

In addition, Lipoprotein (a), or Lp(a), when combined with C-reactive protein, can increase the predictive value of a cardiac event. This is especially true for those who have normal cholesterol levels. The reason is that the lipoprotein promotes vascular inflammation that affects the atherogenic process directly.

Reference

Pagana, K.D., Pagana, T.J. Mosby's Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests, 3rd ed. Mosby Elsvier, 2006.

Recently, the development of a high-sensitivity assay for CRP (hs-CRP) has been made available. The assay works because it can accurately reflect even low levels of CRP. There have been quite a few prospective studies that have shown that an assay of a baseline CRP can be used as a marker for cardiovascular events.

When patients have a test that shows elevated levels, it is even a better marker than LDL cholesterol for predicting events such as myocardial infarction. An elevated test, however, can also mean hypertension, metabolic syndrome or diabetes, or a chronic infection.

In addition, Lipoprotein (a), or Lp(a), when combined with C-reactive protein, can increase the predictive value of a cardiac event. This is especially true for those who have normal cholesterol levels. The reason is that the lipoprotein promotes vascular inflammation that affects the atherogenic process directly.

Reference

Pagana, K.D., Pagana, T.J. Mosby's Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests, 3rd ed. Mosby Elsvier, 2006.

Labels:

nutr therap

How to Rid Yourself of Statin-induced Muscle Pain

When a patient is on a statin, nutritionists should advise that they don’t have to suffer from the side effects of statin-associated muscle pain (myalgia). Studies are showing that supplementation with two key compounds are useful for decreasing the pain. The first is ubiquinone (coenzyme Q10, coQ10) and the other is cholecalciferol (vitamin D3).

Statins such as Lipitor, Zocor and Mevacor reduce cholesterol synthesis by directly inhibiting the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase and deplete production of its product, mevalonate (1). Mevalonite, however, is also the precursor to coQ10 and squalene. Both of these are vital nutrients with profound effects on the body.

CoQ10

CoQ10 is a lipid-soluble antioxidant playing a protective effect in the membranes of every cell in the body. In that capacity, it serves to protect against oxidative damage to cells. Equally important, the compound is necessary for electron transfer in the mitochondrial electron transport chain for producing energy (2). Without it, our muscles could not function in their full capacity.

Supplementation with coQ10 combined with statin treatment helps reduce muscle pain (not to mention improve energy levels). According to a double-blind study in 2007 at Stony Brook University, which compared coQ10 supplementation (100mg/d) with vitamin E (400 IU/d), showed that patients taking the coQ10 had 40 percent decrease in the severity of their pain (3).

Vitamin D

Squalene is important because it is the precursor for 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) as well as other steroid hormones. For this reason that, it is suggested that statin drugs can lead to 25(OH)D insufficiency or deficiency. Vitamin D is not only critical for speeding up calcium absorption for bone health, but emerging studies are finding that it’s also vital for the health of muscles (4).

Low vitamin D levels are also associated with statin-induced muscle pain. When researchers from the Cholesterol Center at the Jewish Hospital in Cincinnatti in Ohio treated myalgia in 38 statin-treated patients with vitamin D (50,000 IU/week for 12 weeks), 35 of the patients experienced 92 percent reduction in pain symptoms (5).

Reducing muscle pain with supplementation

If you must take a statin, then supplementation can be to your advantage. As in the studies, supplementation with coQ10 at 100 mg in an absorbable form can potentially help to keep pain under control by replenishing coQ10 that is lost. In addition, keeping 25(OH)D to levels in the plasma to “sufficient” amounts (32 ng/mL) through supplementation with vitamin D and sensible sun exposure can go far to reduce pain.

Reference List

1. Scharnagl H, Marz W. New lipid-lowering agents acting on LDL receptors. Curr Top Med Chem 2005;5:233-42.

2. Jeya M, Moon HJ, Lee JL, Kim IW, Lee JK. Current state of coenzyme Q(10) production and its applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010;85:1653-63.

3. Caso G, Kelly P, McNurlan MA, Lawson WE. Effect of coenzyme q10 on myopathic symptoms in patients treated with statins. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1409-12.

4. Visvanathan R, Chapman I. Preventing sarcopaenia in older people. Maturitas 2010.

5. Ahmed W, Khan N, Glueck CJ et al. Low serum 25 (OH) vitamin D levels (<32 ng/mL) are associated with reversible myositis-myalgia in statin-treated patients. Transl Res 2009;153:11-6.

Statins such as Lipitor, Zocor and Mevacor reduce cholesterol synthesis by directly inhibiting the enzyme HMG-CoA reductase and deplete production of its product, mevalonate (1). Mevalonite, however, is also the precursor to coQ10 and squalene. Both of these are vital nutrients with profound effects on the body.

CoQ10

CoQ10 is a lipid-soluble antioxidant playing a protective effect in the membranes of every cell in the body. In that capacity, it serves to protect against oxidative damage to cells. Equally important, the compound is necessary for electron transfer in the mitochondrial electron transport chain for producing energy (2). Without it, our muscles could not function in their full capacity.

Supplementation with coQ10 combined with statin treatment helps reduce muscle pain (not to mention improve energy levels). According to a double-blind study in 2007 at Stony Brook University, which compared coQ10 supplementation (100mg/d) with vitamin E (400 IU/d), showed that patients taking the coQ10 had 40 percent decrease in the severity of their pain (3).

Vitamin D

Squalene is important because it is the precursor for 25 hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) as well as other steroid hormones. For this reason that, it is suggested that statin drugs can lead to 25(OH)D insufficiency or deficiency. Vitamin D is not only critical for speeding up calcium absorption for bone health, but emerging studies are finding that it’s also vital for the health of muscles (4).

Low vitamin D levels are also associated with statin-induced muscle pain. When researchers from the Cholesterol Center at the Jewish Hospital in Cincinnatti in Ohio treated myalgia in 38 statin-treated patients with vitamin D (50,000 IU/week for 12 weeks), 35 of the patients experienced 92 percent reduction in pain symptoms (5).

Reducing muscle pain with supplementation

If you must take a statin, then supplementation can be to your advantage. As in the studies, supplementation with coQ10 at 100 mg in an absorbable form can potentially help to keep pain under control by replenishing coQ10 that is lost. In addition, keeping 25(OH)D to levels in the plasma to “sufficient” amounts (32 ng/mL) through supplementation with vitamin D and sensible sun exposure can go far to reduce pain.

Reference List

1. Scharnagl H, Marz W. New lipid-lowering agents acting on LDL receptors. Curr Top Med Chem 2005;5:233-42.

2. Jeya M, Moon HJ, Lee JL, Kim IW, Lee JK. Current state of coenzyme Q(10) production and its applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010;85:1653-63.

3. Caso G, Kelly P, McNurlan MA, Lawson WE. Effect of coenzyme q10 on myopathic symptoms in patients treated with statins. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1409-12.

4. Visvanathan R, Chapman I. Preventing sarcopaenia in older people. Maturitas 2010.

5. Ahmed W, Khan N, Glueck CJ et al. Low serum 25 (OH) vitamin D levels (<32 ng/mL) are associated with reversible myositis-myalgia in statin-treated patients. Transl Res 2009;153:11-6.

Labels:

nutr therap

Atheism is a recent Neolithic invention: Ancestral humans were spiritual people

For the sake of simplicity, this post treats “atheism” as synonymous with “non-spiritualism”. Technically, one can be spiritual and not believe in any deity or supernatural being, although this is not very common. This post argues that atheism is a recent Neolithic invention; an invention that is poorly aligned with our Paleolithic ancestry.

Our Paleolithic ancestors were likely very spiritual people; at least those belonging to the Homo sapiens species. Earlier ancestors, such as the Australopithecines, may have lacked enough intelligence to be spiritual. Interestingly, often atheism is associated with high intelligence and a deep understanding of science. Many well-known, and brilliant, evolution researchers are atheists (e.g., Richard Dawkins).

Well, when we look at our ancestors, spirituality seems to have emerged as a result of increased intelligence.

Spirituality can be seen in cave paintings, such as the one below, from the Chauvet Cave in southern France. The Chauvet Cave is believed to have the earliest known cave paintings, dating back to about 30 to 40 thousand years ago. The painting below is on the cover of the book Dawn of art: The Chauvet Cave. (See the full reference for this publication and others at the end of this post.)

The most widely accepted theory of the origin of cave paintings is that they were used in shamanic or religious rituals. By and large, they were not used to convey information (e.g., as maps); and they are often found deep in caves, in areas that are almost inaccessible, ruling out a “decorative” artistic purpose. As De La Croix and colleagues (1991) note:

Isolated hunter-gatherers also provide a glimpse at our spiritual Paleolithic past. No isolated hunter-gatherer group has ever been found in which atheism was the predominant belief among its members. In fact, the life of most isolated hunter-gatherer groups that have been studied appears to have revolved around religious rituals. In many of these groups, shamans held a very high social status, and strongly influenced group decisions.

Finally, there is solid empirical evidence from human genetics and the study of modern human groups that: (a) “religiosity” may be coded into our genes, to a larger extent in some individuals than in others; and (b) those who are spiritual, particularly those who belong to a spiritual or religious group, have generally better health and experience lower levels of depression and stress (which likely influence health) than those who do not.

There was once an ape that became smart. It invented weapons, which greatly multiplied the potential for death and destruction of the ape’s natural propensity toward violence; violence often motivated by different religious and cultural beliefs held by different groups. It also invented delicious foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars, which slowly poisoned the ape’s body.

Could the recent invention of atheism have been just as unhealthy?

Surely religion has been at the source of conflicts that have caused much death and destruction. But is religion, or spirituality, really to be blamed? Many other factors can lead to a great deal of death and destruction, sometimes directly, other times indirectly – e.g., poverty and illiteracy.

References:

Brown, D.E. (1991). Human universals. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Chauvet, J.M., Deschamps, E.B., & Hillaire, C. (1996). Dawn of art: The Chauvet Cave. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams.

De La Croix, H., Tansey, R.G., & Kirkpatrick, D. (1991). Gardner’s art through the ages: Ancient, medieval, and non-European art. Philadelphia, PA: Harcourt Brace.

Gombrich, E.H. (2006). The story of art. London, England: Pheidon Press.

Murdock, G.P. (1958). Outline of world cultures. New Haven, CN: Human Relations Area Files Press.

Our Paleolithic ancestors were likely very spiritual people; at least those belonging to the Homo sapiens species. Earlier ancestors, such as the Australopithecines, may have lacked enough intelligence to be spiritual. Interestingly, often atheism is associated with high intelligence and a deep understanding of science. Many well-known, and brilliant, evolution researchers are atheists (e.g., Richard Dawkins).

Well, when we look at our ancestors, spirituality seems to have emerged as a result of increased intelligence.

Spirituality can be seen in cave paintings, such as the one below, from the Chauvet Cave in southern France. The Chauvet Cave is believed to have the earliest known cave paintings, dating back to about 30 to 40 thousand years ago. The painting below is on the cover of the book Dawn of art: The Chauvet Cave. (See the full reference for this publication and others at the end of this post.)

The most widely accepted theory of the origin of cave paintings is that they were used in shamanic or religious rituals. By and large, they were not used to convey information (e.g., as maps); and they are often found deep in caves, in areas that are almost inaccessible, ruling out a “decorative” artistic purpose. As De La Croix and colleagues (1991) note:

Researchers have evidence that the hunters in the caves, perhaps in a frenzy stimulated by magical rites and dances, treated the painted animals as if they were alive. Not only was the quarry often painted as pierced by arrows, but hunters actually may have thrown spears at the images, as sharp gouges in the side of the bison at Niaux suggest.Niaux is another cave in southern France. Like the Chauvet Cave, it is full of prehistoric paintings. Even though those paintings are believed to be more recent, dating back to the end of the Paleolithic, they follow the same patterns seen almost everywhere in prehistoric art. The patterns point at a life that gravitates around spiritual rituals.

Isolated hunter-gatherers also provide a glimpse at our spiritual Paleolithic past. No isolated hunter-gatherer group has ever been found in which atheism was the predominant belief among its members. In fact, the life of most isolated hunter-gatherer groups that have been studied appears to have revolved around religious rituals. In many of these groups, shamans held a very high social status, and strongly influenced group decisions.

Finally, there is solid empirical evidence from human genetics and the study of modern human groups that: (a) “religiosity” may be coded into our genes, to a larger extent in some individuals than in others; and (b) those who are spiritual, particularly those who belong to a spiritual or religious group, have generally better health and experience lower levels of depression and stress (which likely influence health) than those who do not.

There was once an ape that became smart. It invented weapons, which greatly multiplied the potential for death and destruction of the ape’s natural propensity toward violence; violence often motivated by different religious and cultural beliefs held by different groups. It also invented delicious foods rich in refined carbohydrates and sugars, which slowly poisoned the ape’s body.

Could the recent invention of atheism have been just as unhealthy?

Surely religion has been at the source of conflicts that have caused much death and destruction. But is religion, or spirituality, really to be blamed? Many other factors can lead to a great deal of death and destruction, sometimes directly, other times indirectly – e.g., poverty and illiteracy.

References:

Brown, D.E. (1991). Human universals. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Chauvet, J.M., Deschamps, E.B., & Hillaire, C. (1996). Dawn of art: The Chauvet Cave. New York, NY: Harry N. Abrams.

De La Croix, H., Tansey, R.G., & Kirkpatrick, D. (1991). Gardner’s art through the ages: Ancient, medieval, and non-European art. Philadelphia, PA: Harcourt Brace.

Gombrich, E.H. (2006). The story of art. London, England: Pheidon Press.

Murdock, G.P. (1958). Outline of world cultures. New Haven, CN: Human Relations Area Files Press.

Thursday, May 20, 2010

Cheese’s vitamin K2 content, pasteurization, and beneficial enzymes: Comments by Jack C.

The text below is all from commenter Jack C.’s notes on this post summarizing research on cheese. My additions are within “[ ]”. While the comments are there under the previous post for everyone to see, I thought that they should be in a separate post. Among other things, they provide an explanation for the findings summarized in the previous post.

During [the] cheese fermentation process the vitamin K2 (menaquinone) content of cheese is increased more than ten-fold. Vitamin K2 is anti-carcinogenic, reduces calcification of soft tissue (like arteries) and reduces bone fracture risk. So vitamin K2 in aged cheese provides major health benefits that are not present in the control nutrients. [Jack is referring to the control nutrients used in the study summarized in the previous post.]

Another apparent benefit of aged cheese is the breakdown of the peptide BCM7 (beta-casomorphin 7) which is present in the casein milk of most cows (a1 milk) in the U.S. BCM7 is a powerful oxidant and is highly atherogenic. (From "Devil in the Milk" by Keith Woodford.)

[P]asteurization is not necessary, for during the aging process, the production of lactic acid results in a drop in pH which destroys pathogenic bacteria but does not harm beneficial bacteria! Many benefits result.

In making aged cheese, the temperature [should] be kept to no more than 102 degrees F, the same temperature that the milk comes out of the cow. The many beneficial enzymes in milk (8 actually) therefore are not harmed and provide many health benefits. Lactoferrin, for example, destroys pathogenic bacteria by binding to iron (most pathogenic bacteria are iron loving) and also helps in absorption of iron. Lipase helps break down fats and reduces the load on the pancreas which produces lipase.

By federal law, milk that has not been pasteurized cannot be shipped across state lines [in the U.S.], but raw milk cheese can be legally shipped provided that it has been aged at least sixty days. Thus, in backward states like Alabama where I live that do not permit the sale of raw milk, you can get the same beneficial enzymes (well, almost) from aged cheese as from raw milk. And as you pointed out, cheese that is shrink-wrapped will keep a long time and can be easily shipped.

I buy most of my raw milk cheese from a small dairy in Elberta, Alabama, Sweet Home Farm, which produces a great variety of organic raw milk cheese from Guernsey cows that are fed nothing but grass. No grain, no antibiotics or growth hormones. There is nothing comparable in the way of milk that is available legally. The so called “organic” milk sold in stores is all ultra-pasteurized. Yuck.

Raw milk cheese is readily shipped. Sweet Home Farm does not ship cheese, so I have to go get it, 70 miles round trip. On occasion I buy raw milk cheese from Next Generation Dairy, a small coop in Minn. which promises that they do not raise the temperature of the cheese to more than 102 degrees F during manufacture. The cheese is modestly priced and can be shipped inexpensively.

Jack

***

During [the] cheese fermentation process the vitamin K2 (menaquinone) content of cheese is increased more than ten-fold. Vitamin K2 is anti-carcinogenic, reduces calcification of soft tissue (like arteries) and reduces bone fracture risk. So vitamin K2 in aged cheese provides major health benefits that are not present in the control nutrients. [Jack is referring to the control nutrients used in the study summarized in the previous post.]

Another apparent benefit of aged cheese is the breakdown of the peptide BCM7 (beta-casomorphin 7) which is present in the casein milk of most cows (a1 milk) in the U.S. BCM7 is a powerful oxidant and is highly atherogenic. (From "Devil in the Milk" by Keith Woodford.)

[P]asteurization is not necessary, for during the aging process, the production of lactic acid results in a drop in pH which destroys pathogenic bacteria but does not harm beneficial bacteria! Many benefits result.

In making aged cheese, the temperature [should] be kept to no more than 102 degrees F, the same temperature that the milk comes out of the cow. The many beneficial enzymes in milk (8 actually) therefore are not harmed and provide many health benefits. Lactoferrin, for example, destroys pathogenic bacteria by binding to iron (most pathogenic bacteria are iron loving) and also helps in absorption of iron. Lipase helps break down fats and reduces the load on the pancreas which produces lipase.

By federal law, milk that has not been pasteurized cannot be shipped across state lines [in the U.S.], but raw milk cheese can be legally shipped provided that it has been aged at least sixty days. Thus, in backward states like Alabama where I live that do not permit the sale of raw milk, you can get the same beneficial enzymes (well, almost) from aged cheese as from raw milk. And as you pointed out, cheese that is shrink-wrapped will keep a long time and can be easily shipped.

I buy most of my raw milk cheese from a small dairy in Elberta, Alabama, Sweet Home Farm, which produces a great variety of organic raw milk cheese from Guernsey cows that are fed nothing but grass. No grain, no antibiotics or growth hormones. There is nothing comparable in the way of milk that is available legally. The so called “organic” milk sold in stores is all ultra-pasteurized. Yuck.

Raw milk cheese is readily shipped. Sweet Home Farm does not ship cheese, so I have to go get it, 70 miles round trip. On occasion I buy raw milk cheese from Next Generation Dairy, a small coop in Minn. which promises that they do not raise the temperature of the cheese to more than 102 degrees F during manufacture. The cheese is modestly priced and can be shipped inexpensively.

Jack

Tuesday, May 18, 2010

Cheese consumption, visceral fat, and adiponectin levels

Several bacteria feed on lactose, the sugar found in milk, producing cheese for us as a byproduct of their feeding. This is why traditionally made cheese can be eaten by those who are lactose intolerant. Cheese consumption predates written history. This of course does not refer to processed cheese, frequently sold under the name “American cheese”. Technically speaking, processed cheese is not “real” cheese.

One reasonably reliable way of differentiating between traditional and processed cheese varieties is to look for holes. Cheese-making bacteria produce a gas, carbon dioxide, which leaves holes in cheese. There are exceptions though, and sometimes the holes are very small, giving the impression of no holes. Another good way is to look at the label and the price; usually processed cheese is labeled as such, and is cheaper than traditionally made cheese.

Cheese does not normally spoil; it ages. When vacuum-wrapped, cheese is essentially in “suspended animation”. After opening it, it is a good idea to store it in such a way as to allow it to “breathe”, or continue aging. Wax paper does a fine job at that. This property, extended aging, has made cheese a very useful source of nutrition for travelers in ancient times. It was reportedly consumed in large quantities by Roman soldiers.

Walther and colleagues (2008) provide a good review of the role of cheese in nutrition and health. The full reference is at the end of this post. They point out empirical evidence that cheese, particularly that produced with Lactobacillus helveticus (e.g., Gouda and Swiss cheese), contributes to lowering blood pressure, stimulates growth and development of lean body tissues (e.g., muscle), and has anti-carcinogenic properties.

The health-promoting effects of cheese were also reviewed by Higurashi and colleagues (2007), who hypothesized that those effects may be in part due to the intermediate positive effects of cheese on adiponectin and visceral body fat levels. They conducted a study with rats that supports those hypotheses.

In the study, they fed two groups of rats an isocaloric diet with 20 percent of fat, 20 percent of protein, and 60 percent of carbohydrate (in the form of sucrose). In one group, the treatment group, Gouda cheese (produced with Lactobacillus helveticus) was the main source of protein. In the other group, the control group, isolated casein was the main source of protein. The researchers were careful to avoid confounding variables; e.g., they adjusted the vitamin and mineral intake in the groups so as to match them.

The table below (click to enlarge) shows initial and final body weight, liver weight, and abdominal fat for both groups of rats. As you can see, the rats more than quadrupled in weight by the end of the 8-weight experiment! Abdominal fat was lower in the cheese group; one type of visceral fat, mesenteric, was significantly lower. Whole body weight-adjusted liver weight was higher in the cheese group. Liver weight increase is often associated with increased muscle mass. The rats in the cheese group were a little heavier on average, even though they had less abdominal fat.

The figure below shows adiponectin levels at the 4-week and 8-week marks. While adiponectin levels decreased in both groups, which was to be expected given the massive gain in weight (and probably body fat mass), only in the casein group the decrease in adiponectin was significant. In fact, the relatively small decrease in the cheese group is a bit surprising given the increase in weight observed.

If we could extrapolate these findings to humans, and this is a big “if”, one could argue that cheese has some significant health-promoting effects. There is one small problem with this study though. To ensure that the rats consumed the same number of calories, the rats in the casein group were fed slightly more sucrose. The difference was very small though; arguably not enough to explain the final outcomes.

This study is interesting because the main protein in cheese is actually casein, and also because casein powders are often favored by those wanting to put on muscle as part of a weight training program. This study suggests that the cheese-ripening process induced by Lactobacillus helveticus may yield compounds that are particularly health-promoting in three main ways – maintaining adiponectin levels; possibly increasing muscle mass; and reducing visceral fat gain, even in the presence of significant weight gain. In humans, reduced circulating adiponectin and increased visceral fat are strongly associated with the metabolic syndrome.

One caveat: if you think that eating cheese may help wipe out that stubborn abdominal fat, think again. This is a topic for another post. But, briefly, this study suggests that cheese consumption may help reduce visceral fat. Visceral fat, however, is generally fairly easy to mobilize (i.e., burn); much easier than the stubborn subcutaneous body fat that accumulates in the lower abdomen of middle-aged men and women. In middle-aged women, stubborn subcutaneous fat also accumulates in the hips and thighs.

Could eating Gouda cheese, together with other interventions (e.g., exercise), become a new weapon against the metabolic syndrome?

References:

Higurashi, S., Kunieda, Y., Matsuyama, H., & Kawakami, H. (2007). Effect of cheese consumption on the accumulation of abdominal adipose and decrease in serum adiponectin levels in rats fed a calorie dense diet. International Dairy Journal, 17(10), 1224–1231.

Walther, B., Schmid, A., Sieber, R., & Wehrmüller, K. (2008). Cheese in nutrition and health. Dairy Science Technology, 88(4), 389-405.

One reasonably reliable way of differentiating between traditional and processed cheese varieties is to look for holes. Cheese-making bacteria produce a gas, carbon dioxide, which leaves holes in cheese. There are exceptions though, and sometimes the holes are very small, giving the impression of no holes. Another good way is to look at the label and the price; usually processed cheese is labeled as such, and is cheaper than traditionally made cheese.

Cheese does not normally spoil; it ages. When vacuum-wrapped, cheese is essentially in “suspended animation”. After opening it, it is a good idea to store it in such a way as to allow it to “breathe”, or continue aging. Wax paper does a fine job at that. This property, extended aging, has made cheese a very useful source of nutrition for travelers in ancient times. It was reportedly consumed in large quantities by Roman soldiers.

Walther and colleagues (2008) provide a good review of the role of cheese in nutrition and health. The full reference is at the end of this post. They point out empirical evidence that cheese, particularly that produced with Lactobacillus helveticus (e.g., Gouda and Swiss cheese), contributes to lowering blood pressure, stimulates growth and development of lean body tissues (e.g., muscle), and has anti-carcinogenic properties.

The health-promoting effects of cheese were also reviewed by Higurashi and colleagues (2007), who hypothesized that those effects may be in part due to the intermediate positive effects of cheese on adiponectin and visceral body fat levels. They conducted a study with rats that supports those hypotheses.

In the study, they fed two groups of rats an isocaloric diet with 20 percent of fat, 20 percent of protein, and 60 percent of carbohydrate (in the form of sucrose). In one group, the treatment group, Gouda cheese (produced with Lactobacillus helveticus) was the main source of protein. In the other group, the control group, isolated casein was the main source of protein. The researchers were careful to avoid confounding variables; e.g., they adjusted the vitamin and mineral intake in the groups so as to match them.