Like most animals, our Paleolithic ancestors had to regularly undergo short periods of low calorie intake. If they were successful at procuring food, those ancestors alternated between periods of mild famine and feast. As a result, nature allowed them to survive and leave offspring. The periods of feast likely involved higher-than-average consumption of animal foods, with the opposite probably being true in periods of mild famine.

Almost anyone who adopted a low carbohydrate diet for a while will tell you that they find foods previously perceived as bland, such as carrots or walnuts, to taste very sweet – meaning, to taste very good. This is a special case of a more general phenomenon. If a nutrient is important for your body, and your body is deficient in it, those foods that contain the nutrient will taste very good.

This rule of thumb applies primarily to foods that contributed to selection pressures in our evolutionary past. Mostly these were foods available in our Paleolithic evolutionary past, although some populations may have developed divergent partial adaptations to more modern foods due to recent yet acute selection pressure. Because of the complexity of the dietary nutrient absorption process, involving many genes, I suspect that the vast majority of adaptations to modern foods are partial adaptations.

Modern engineered foods are designed to bypass reward mechanisms that match nutrient content with deficiency levels. That is not the case with more natural foods, which tend to taste good only to the extent that the nutrients that they carry are needed by our bodies.

Consequently palatability is not fixed for a particular natural food; it does not depend only on the nutrient content of the food. It also depends on the body’s deficiency with respect to the nutrient that the food contains. Below is what you would get if you were to plot a surface that best fit a set of data points relating palatability of a specific food item, nutrient content of that food, and the level of nutrient deficiency, for a group of people. I generated the data through a simple simulation, with added error to make the simulation more realistic.

Based on this best-fitting surface you could then generate a contour graph, shown below. The curves are “contour lines”, a.k.a. isolines. Each isoline refers to palatability values that are constant for a set of nutrient content and nutrient deficiency combinations. Next to the isolines are the corresponding palatability values, which vary from about 10 to 100. As you can see, palatability generally goes up as one moves toward to right-top corner of the graph, which is the area where nutrient content and nutrient deficiency are both high.

What happens when the body is in short-term nutrient deficiency with respect to a nutrient? One thing that happens is an increase in enzymatic activity, often referred to by the more technical term “phosphorylation”. Enzymes are typically proteins that cause an acute and targeted increase in specific metabolic processes. Many diseases are associated with dysfunctional enzyme activity. Short-term nutrient deficiency causes enzymatic activity associated with absorption and retention of the nutrient to go up significantly. In other words, your body holds on to its reserves of the nutrient, and becomes much more responsive to dietary intake of the nutrient.

The result is predictable, but many people seem to be unaware of it; most are actually surprised by it. If the nutrient in question is a macro-nutrient, it will be allocated in such a way that less of it will go into our calorie stores – namely adipocytes (body fat). This applies even to dietary fat itself, as fat is needed throughout the body for functions other than energy storage. I have heard from many people who, by alternating between short-term fasting and feasting, lost body fat while maintaining the same calorie intake as in a previous period when they were steadily gaining body fat without any fasting. Invariably they were very surprised by what happened.

In a diet of mostly natural foods, with minimal intake of industrialized foods, short-term calorie deficiency is usually associated with short-term deficiency of various nutrients. Short-term calorie deficiency, when followed by significant calorie surplus (i.e., eating little and then a lot), is associated with a phenomenon I blogged about before here – the “14-percent advantage” of eating little and then a lot (, ). Underfeeding and then overfeeding leads to a reduction in the caloric value of the meals during overfeeding; a reduction of about 14 percent of the overfed amount.

So, how can you go through the Holiday Season giving others the impression that you eat as much as you want, and do not gain any body fat (maybe even lose some)? Eat very little, or fast, in those days where there will be a feast (Thanksgiving dinner); and then eat to satisfaction during the feast, staying away from industrialized foods as much as possible. Everything will taste extremely delicious, as nature’s “special spice” is hunger. And you may even lose body fat in the process!

But there is a problem. Our bodies are not designed to associate eating very little, or not at all, with pleasure. Yet another thing that we can blame squarely on evolution! Success takes practice and determination, aided by the expectation of delayed gratification.

Monday, November 26, 2012

Monday, November 19, 2012

AMOUR

“...the unavoidability of death is a matter frequently evaded by euphemism and clouded by sentimentality.”

I am away for much of the next few weeks, so this blog may fluctuate a little. I did however, want to just write a few words about mortality before I vanish. I’m currently working with my colleagues Steven Gartside, Zoe Watson and Valeria Ruiz Vargas to curate an extraordinary exhibition here at in Manchester’s Holden Gallery, next July. The exhibition will bring together the work of some iconic contemporary artists whose work touches upon Mortality: Death and the Imagination.

With our work unfolding, and the commitment of some great artists and thinkers of our time, who I'll announce very soon, its not surprising I noticed that the film critic Philip French had written a stunning review of a film I haven't yet seen, but which leaves me with such anticipation, I must flag it up. I’m taking a punt on something that my instincts (and now the critics) tells me, sounds quite unique. Amour is a film by Michael Haneke, and French believes it will -

“...take its place alongside the greatest films about the confrontation of ageing and death, among them Ozu's Tokyo Story, Kurosawa's Living, Bergman's Wild Strawberries, Rosi's Three Brothers and, dare I say it, Don Siegel's The Shootist. It's worthy of being discussed in the same breath as the novels and plays of Samuel Beckett, of which Christopher Ricks wrote in his bitingly perceptive Beckett's Dying Words: "We know about our wish to go on being, we human beings, our wish not to die. Samuel Beckett, who rigged nothing, fashioned for himself and for us a voice, Malone's, at once wistful and wiry: 'Yes, there is no good pretending, it is hard to leave everything.' These are the accents of a consciousness, imagining and imagined, which braves the immortal commonplace of mortality."

I'll leave you to read his full article by clicking here, and watch the trailer for the film above.

If life permits, I will attempt to blog something from the fourth Arts of Good Health and Wellbeing conference in Fremantle.

Thank you as ever for following the blog...C.P.

Monday, November 12, 2012

...the BIG BANG

So here are some of your thoughts on part one of manifesto - all red and green - and yes of course, in glorious Black and White too!

It's here for you to digest and g r o a n o v e r - what, no bullet points - no action plan - a nice little framework perhaps?

No, NO a thousand times NO. You can pick one of those up from any fly-by-night, five-a-day, quick fix consultants. In for a penny, in for a pound. £

Grease me palm with your hard fought-for coffers and I'll tell you what you want to hear. Elixirs, miracle cures? The arts'll solve it all - heal your wounds, cure your aches and pains and tuck you up in your bed at night?

Instrumental - temperamental? Fine art - pop art? Reductionist - Irrationalist?

It's a point in time. Histrionics? Maybe - but born full-term and bursting for a fight.

Enlightened and Romantic without a seconds glance back to your bean counting gibberish..."we want to weight it, measure it and standardise the little beauty."

Oh, but the market my dear, the fragile economy, the BIG things, the STUFF... the words and important THINGS about our fiscal state - of policy being informed by the finest STUFF...you know: research informed policy! Yes that's it, policy made on the basis of the finest research - ahhh the randomised controlled trial - the GOLD standard...a model of pharmacological impartiality and rigorous analysis - the midas touch.

Oh yes, that's the one - only it's not - and has no pretensions to be - it's a baby; a big FAT baby, born of a 1000+ loving parents!

A thousand mothers and fathers thrown into the gene pool...the progeny and lineage are all messed up. There’s my none-too-perfect DNA and yours too.

Beautiful hybrid eh?

...and is it a Northern child, ruddy cheeked and all flat vowels? Is it European? Eurasian? Venusian? It's an exotic little fellow...and it's still mutating....

Have a cup of coffee - a glass of red - better still, a bottle of water

Go On...A Toast! To you, and you and us...

Where to now for this baby? We need to bring it up, of course...how we do it - well, its for us to decide...

mmmmmmm, how will we do it?

SCENARIOS, SCENARIOS - lets start to imagine some scenarios

S C E N A R I O S: in arts, health and wellbeing JANUARY 2013 across our

GLORIOUS NORTHERN LANDS...

dates coming soon...

The bipolar disorder pendulum: Depression as a compensatory adaptation

As far as explaining natural phenomena, Darwin was one of the best theoretical researchers of all time. Yet, there were a few phenomena that puzzled him for many years. One was the evolution of survival-impairing traits such as the peacock’s train, the large and brightly colored tail appendage observed in males.

Tha male peacock’s train is detrimental to the animal’s survival, and yet it is clearly an evolved trait ().

This type of trait is known as a “costly” trait – a trait that enhances biological fitness (or reproductive success, not to be confused with “gym fitness”), and yet is detrimental to the survival of the individuals who possess it (). Many costly traits have evolved in animals because of sexual selection. That is, they have evolved because they are sexy.

Costly traits seem like a contradiction in terms, but the mechanisms by which they can evolve become clear when evolution is modeled mathematically (, ). There is evidence that mental disorders may have evolved as costs of attractive mental traits (); one in particular, bipolar disorder (a.k.a. manic-depression), fits this hypothesis quite well.

Ironically, a key contributor to the mathematics used to understand costly traits, George R. Price (), might have suffered from severe bipolar disorder. Most of Price’s work in evolutionary biology was done in the 1970s; toward the end of his life, which was untimely ended by Price himself. For many years he was known mostly by evolutionary biologists, but this has changed recently with the publication of Oren Harman’s superb biographical book titled “The Price of Altruism: George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness” ().

Bipolar disorder is a condition characterized by disruptive mood swings. These swings are between manic and depressed states, and are analogous to the movement of a pendulum in that they alternate, seemingly gravitating around the "normal" state. See the figurative pendulum representation below, adapted from a drawing on Thinkquest.org.

Bipolar disorder is generally associated with creative intelligence, which is a very attractive trait (). Moreover, the manic state of the disorder is associated with hypersexuality and exaggerated generosity (). So one can clearly see how having bipolar disorder may lead to greater reproductive success, even as it creates long-term survival problems.

On one hand, a person may become very energetic and creative while in the manic state. This could be one of the reasons why many who suffer from bipolar disorder have fairly successful careers in fields that require creative intelligence (), which are many and not restricted to fields related to the fine and performing arts. Creative intelligence is highly valued in most knowledge-intensive professions ().

On the other hand, sustained acute mania or depression are frequently associated with serious health problems (). This is why the clinical treatment of bipolar disorder often starts with an attempt to keep the pendulum from moving too far in one direction or another. This may require medication, such as clinical doses of the elemental salt lithium, prior to cognitive behavioral therapy. The focus of cognitive behavioral therapy is on changing the way one sees and thinks about the world, particularly one’s “social world”.

Prolonged acute mania, usually accompanied by severely impaired sleep, may lead to psychosis. This, psychosis, is an extreme state characterized by hallucinations and/or delusions, leading to hospitalization in most cases. It has been theorized that depression is an involuntary compensatory adaptation () aimed at moving the pendulum in the other direction, out of the manic state, before more damage ensues ().

Elaborate approaches have been devised to treat and manage bipolar disorder treatment that involve the identification of mania and depression “prodromes” (), which are signs that a full-blown manic or depressive episode is about to start. Once prodromes are identified, cognitive behavioral therapy techniques are employed to prevent the pendulum from moving further in one direction or the other. The main goal of these techniques is to change one’s way of thinking about various issues (e.g., fears, pessimism). These techniques take years of practice to be used effectively.

Identification of prodromes and subsequent use of cognitive behavioral therapy seems to be particularly effective when dutifully applied with respect to manic episodes (). The reason for this may be related to one interesting fact related to bipolar disorder: manic episodes are not normally dreaded as much as depression episodes.

In fact, many sufferers avoid taking medication because they do not want to give up the creative and energetic bursts that come with manic episodes, even though they absolutely do not want the pendulum to go in the other direction. The problem is that, if depression is indeed a compensatory adaptation to mania, it seems reasonable to assume that extreme manic episodes are likely to be followed by extreme episodes of depression. Perhaps the key to avoid prolonged acute depression is to avoid prolonged acute mania.

As someone with bipolar disorder becomes more and more excited with novel and racing thoughts (a prodrome of mania), it would probably make sense to identify and carry out calming activities – to avoid a fall into despairing depression afterwards.

Tha male peacock’s train is detrimental to the animal’s survival, and yet it is clearly an evolved trait ().

This type of trait is known as a “costly” trait – a trait that enhances biological fitness (or reproductive success, not to be confused with “gym fitness”), and yet is detrimental to the survival of the individuals who possess it (). Many costly traits have evolved in animals because of sexual selection. That is, they have evolved because they are sexy.

Costly traits seem like a contradiction in terms, but the mechanisms by which they can evolve become clear when evolution is modeled mathematically (, ). There is evidence that mental disorders may have evolved as costs of attractive mental traits (); one in particular, bipolar disorder (a.k.a. manic-depression), fits this hypothesis quite well.

Ironically, a key contributor to the mathematics used to understand costly traits, George R. Price (), might have suffered from severe bipolar disorder. Most of Price’s work in evolutionary biology was done in the 1970s; toward the end of his life, which was untimely ended by Price himself. For many years he was known mostly by evolutionary biologists, but this has changed recently with the publication of Oren Harman’s superb biographical book titled “The Price of Altruism: George Price and the Search for the Origins of Kindness” ().

Bipolar disorder is a condition characterized by disruptive mood swings. These swings are between manic and depressed states, and are analogous to the movement of a pendulum in that they alternate, seemingly gravitating around the "normal" state. See the figurative pendulum representation below, adapted from a drawing on Thinkquest.org.

Bipolar disorder is generally associated with creative intelligence, which is a very attractive trait (). Moreover, the manic state of the disorder is associated with hypersexuality and exaggerated generosity (). So one can clearly see how having bipolar disorder may lead to greater reproductive success, even as it creates long-term survival problems.

On one hand, a person may become very energetic and creative while in the manic state. This could be one of the reasons why many who suffer from bipolar disorder have fairly successful careers in fields that require creative intelligence (), which are many and not restricted to fields related to the fine and performing arts. Creative intelligence is highly valued in most knowledge-intensive professions ().

On the other hand, sustained acute mania or depression are frequently associated with serious health problems (). This is why the clinical treatment of bipolar disorder often starts with an attempt to keep the pendulum from moving too far in one direction or another. This may require medication, such as clinical doses of the elemental salt lithium, prior to cognitive behavioral therapy. The focus of cognitive behavioral therapy is on changing the way one sees and thinks about the world, particularly one’s “social world”.

Prolonged acute mania, usually accompanied by severely impaired sleep, may lead to psychosis. This, psychosis, is an extreme state characterized by hallucinations and/or delusions, leading to hospitalization in most cases. It has been theorized that depression is an involuntary compensatory adaptation () aimed at moving the pendulum in the other direction, out of the manic state, before more damage ensues ().

Elaborate approaches have been devised to treat and manage bipolar disorder treatment that involve the identification of mania and depression “prodromes” (), which are signs that a full-blown manic or depressive episode is about to start. Once prodromes are identified, cognitive behavioral therapy techniques are employed to prevent the pendulum from moving further in one direction or the other. The main goal of these techniques is to change one’s way of thinking about various issues (e.g., fears, pessimism). These techniques take years of practice to be used effectively.

Identification of prodromes and subsequent use of cognitive behavioral therapy seems to be particularly effective when dutifully applied with respect to manic episodes (). The reason for this may be related to one interesting fact related to bipolar disorder: manic episodes are not normally dreaded as much as depression episodes.

In fact, many sufferers avoid taking medication because they do not want to give up the creative and energetic bursts that come with manic episodes, even though they absolutely do not want the pendulum to go in the other direction. The problem is that, if depression is indeed a compensatory adaptation to mania, it seems reasonable to assume that extreme manic episodes are likely to be followed by extreme episodes of depression. Perhaps the key to avoid prolonged acute depression is to avoid prolonged acute mania.

As someone with bipolar disorder becomes more and more excited with novel and racing thoughts (a prodrome of mania), it would probably make sense to identify and carry out calming activities – to avoid a fall into despairing depression afterwards.

Sunday, November 11, 2012

Human vs. chimps: What the "regulome" tells us about meat eating & bigger brains

|

| Source: Greg Wray |

The savanna would mean a new way of life for our ancestors. They'd learn to use tools, communicate with each other using language, and work together to hunt animals for food. Based on fossil evidence and stable isotope data, our hominin ancestors shifted to a diet where meat was a principal energy source about two million years ago. It would be a major shift in diet that coincided with an increase in cranial capacity.

Now, scientists like Greg Wray, a professor of biology at Duke University, are beginning to better understand the genetic basis for the adaptation to eating meat and how it guided the development of our larger brains. During his plenary talk at the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing's (CASW) "New Horizons in Science 2012" annual conference in Durham, North Carolina, Wray said that the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) project gave scientists like himself a "detailed street map" for seeking out the genetic changes that took place since the divergence of humans and chimpanzees over evolutionary time.

Wray said that the major diet shift to meat eating is written right into the "software" that runs our genes: the regulome. Previous to ENCODE, these non-coding regulatory regions were thought of only as "junk" DNA. In this new post-ENCODE, however, scientists are finding that these regions have central regulatory roles in the genome and may play a central role in adaptation and divergence of species.

In the regulome, Wray said, his lab found that evidence of genetic changes resulting from our ancestors' change in diet that would mean stark differences in how we metabolize fats and sugars in comparison to chimpanzees. The genetic changes could also explain how we're able to feed our energy-hungry brains and why we are more susceptible to specific diseases such as diabetes.

Mini-ENCODE for humans and chimps

The lab focused their research on five tissue samples because of their importance in understanding dietary adaptations—cerebral cortex, cerebellum, liver, adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle. The research would be like a "mini-ENCODE" comparing evolutionary changes between humans and chimpanzees since their divergence from a last common ancestor.

According to Wray, his lab found a "huge signal" of changes in cell signaling genes that meant a lot of coordination going on between metabolism, development, and neural functions. For example, of the 61 genes that are known participants in insulin signaling, 31, almost half, were different. The differences in insulin signaling genes may explain why humans are so much more susceptible to diet-related diseases such as type 1 and 2 diabetes than are chimpanzees. "That's what's changed between humans and chimps," he said.

What's not changed are more general functions involved in DNA transcription, replication, and repair; RNA processing and translation; and protein translation and localization.

Looking at general patterns, Wray also found a lot of signals for metabolism and neural function changes. When humans are compared to rhesus macaques, the changes are still clear along the longer evolutionary span. However, comparing chimps to rhesus macaques finds that the neural signaling is gone while the metabolism signal is still there.

"If you do this kind of analysis for these functional categories, you can start to parse out what's different about human evolution versus other aspects of primate evolution," Wray said.

Fat cells behave differently in humans versus chimps

In humans versus chimps, Wray said, there are also stark differences in how we store fat, produce fat, (de novo synthesis of fatty acids) and how we burn fat for energy (beta-oxidation) because of differently regulated genes. "Pretty much every aspect of fat cell function has been altered between humans and chimps," Wray said.

Investigating further, Wray's lab used adipose tissue stem cells from humans and from chimps and performed a series of petri dish experiments. The cells were grown "under different diets"—that is to say that they grew in the presence of either more carbohydrate, oleic acid (which is the dominant fatty acid found in meat), or linoleic acid (the dominant fatty acid found in grains).

A clear signal was returned: each of the enzymes for fatty acid synthesis was higher among the human adipose tissue cells. In a habitat where the principal energy source would switch from simple sugars from fruit to fatty acids from meat, it'd make sense to have these enzymes upregulated. The findings could explain how humans were able to grow brains thrice the size.

"If you're going to make a bigger brain, a brain that's about three times larger than the chimp-human ancestor, you need to make a whole lot more building material," he said. "You don't need to just make these membrane materials you need to constantly turn them over. So the flux through this pathway is probably pretty important to building a bigger brain."

Although with the reward of a bigger brain through an adaptation to push more fatty acids through pathways came an unintended side effect, Wray said. Another major shift in diet at the agricultural revolution would introduce a large amount of omega-6 fatty acids. A high influx of omega-6 fatty acids would produce higher levels of arachidonic acid, involved in production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids implicated in insulin resistance and atherosclerosis.

Expensive-tissue hypothesis at the metabolic level

Making larger brains came with other costs, as well, and it had to do with a tradeoff of energy allocation. The brain is an exceptionally energy-hungry tissue consuming almost 10-fold higher than the rest of the body even while asleep. "What that means is that if you triple the size of the brain, you’re not making one organ a little bigger, you're essentially raising the energy budget of the body by a lot," Wray said.

As anthropologists and physiologists have long argued, a larger brain meant taking energy away from somewhere else, preferably another energy-hungry tissue. "Expensive-tissue hypothesis" may be partly explained by the fact that our human guts are a little shorter and our muscles are smaller than that of chimpanzees. But it's "not enough," Wray said. His lab suggests that the regulome could explain the tradeoff from a metabolic and molecular level, not at the level of gross organ size.

Sugar transporters show signals of positive selection in the regulatory region, Wray said. A couple of genes called SLC2a1 and SLC2a4 (SLC – transport protein; 2 – sugar transport; a1 and a4 and so forth are different members of those families) are uniquely positioned to mediate the tradeoff. SLC2a1 is expressed predominantly in the brain and SLC2a4 is expressed predominantly in the skeletal muscle.

"We hypothesized that if you increase the expression of the brain transporter and decrease the expression of the muscle transporter, the common point of energy metabolism (glucose)—is going to be allocated differently, just by mass action" Wray said.

What Wray's lab found was that when they compared brain specific expression of the sugar transporter, it was much higher in humans than it was in chimps and rhesus macaques. In muscle, conversely, it's higher in chimpanzees than it is in humans. Double the glucose transporters in the brain and half in the muscle would mean a four-fold difference in glucose getting across the membrane into the brain. As a way of maximizing energy supply to the brain "that's pretty large change," Wray said.

Comparatively, it is well known in the medical field that children with deficiencies in glucose transporters (Glut1 deficiency syndrome) have cognitive deficits. "The brain literally starves," Wray said. "We had to have that increase [in glucose transporters] in the metabolic scope of the brain to allow it to get bigger."

Of mice and bigger brains

During the last few minutes of his talk, Wray shared with his audience one other project his lab was working on, shared as a teaser: It was to clone out pieces of the regulome thought to be responsible for changes in human and chimp brains and testing them in mice embryos.

Wray's lab found that mice embryos with either the "chimp enhancers" or the "human enhancers" had strong signals of neural stem cells production and greater neuron production. In particular, the embryos with the human enhancers came on stronger and lasted longer.

"What we haven't done yet is see what happens if these mice grow up and see if they have cognitive changes, behavioral changes, or detail changes in the structure of their brains," Wray said. Those big-brained mice are going to grow up?

Questions and FADS

After Wray's talk, there were plenty of questions asked by his audience, who were mainly science writers attending Science Writers 2012 (see Keith Eric Grant's #sciwri12 Storify story). These included ones about his own diet -- less starch, some animal products, mostly fruits and vegetables, a higher omega-3 to omega-6 ratio -- and how Richard Wrangham hypothesis that cooking could explain energy tradeoff might've figured into the equation -- yes, Wray agreed, cooked food is easier to digest and absorb.

There was also a question about whether or not Wray's lab would be looking at comparing the human regulomes with that of other hominin species such as Denisovan and Neandertal. It was something, Wray said, that he was definitely looking into doing in the future.

One of the questions I asked Wray was about genetic variation between different human populations, specifically with regards to the FADS region of the genome. The region has been subject of special interest and speculation among researchers because variations of rate-limiting enzymes encoded by FADS1 and FADS2 for biosynthesizing long-chaing fatty acids may also help explain larger brains.

"I think it's a layered processing," he said. "Originally, there was probably upregulation of the FADS genes simply because we had so much more fatty acids in our diet. That probably coincided with the shift to a more animal-rich diet."

Wray added that because both the omega-6s and omega-3s flow through enzymes encoded by the FADS region, it also may explain why a post-agricultural revolution diet higher in grains puts us at higher risk of chronic disease. The high omega-6 to omega-3 ratio of our modern diets puts us "way out of balance," he said, with more omega-6s moving through pathways to produce pro-inflammatory compounds.

Labels:

human evolution,

sciwri12

Friday, November 9, 2012

Food is "star stuff"

|

| Champagne supernova. Credit: Space Daily |

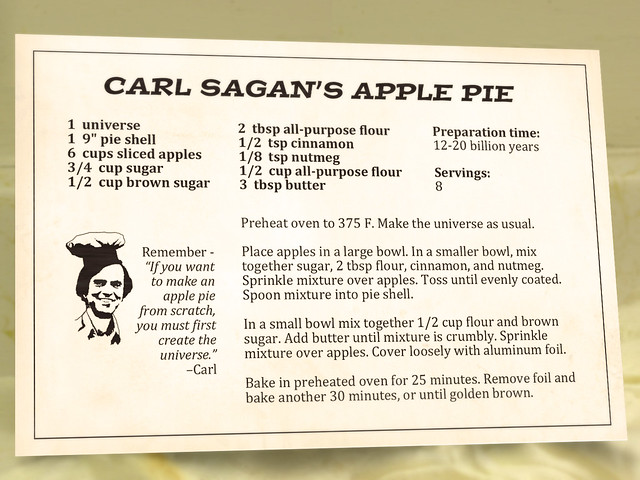

When you eat a slice of apple pie, or any pie, or any food at all today, on Carl Sagan Day, it may be worthwhile to reflect on this quote, one of the beloved television series host's most famous from Cosmos: A Personal Voyage.

A look back at our origins is a good way to gain some perspective, amidst the accumulating scientific evidence, on how to understand our own biology and predicting ways in which we can keep our own healthy. Or, at least, that has been my conclusion. Starting at the beginning with the chemistry of life, our own evolution, and to that of our close cousins, then on to our current situation, and the future, this blog has explored all sorts of topics relating to diet and health in the past and forthcoming.

Over the years, what's evident is that there exist numerous ongoing debates in the world of food, nutrition, and medicine. Some are scientific and some are not so. Frustrations arise. Tension happens. People disagree. That is the nature of progress albeit it can be slow going at times much like evolution.

Sometimes, setting aside any so-called dietary dogmas, one can find some simple peace in the knowledge that all life and our foods are based on basic chemistry. After all, as the father of nutrition Antoine Lavoisier once said, "Life is a chemical process."

In addition, nutritional biochemist Michael Crawford and David Marsh once wrote, that "every particle of matter in the delicate tissues which build our bodies is made of elements that were transmuted into their present form in an unimaginable heat and pressure" (1).

Andy Howell a staff scientist at Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope Network and an adjunct professor of physics at University of California, Santa Barbara is someone who might just have a grasp on the temperature and pressure that furnished our basic elements.

In his entertaining talk, given on dark matter, zombie stars and supernovae at the Science Writers 2012 meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina, Howell gave an overview of the history of physics, the known universe, and then showed models of stellar thermonuclear explosions.

He described how the temperature and pressure in supernovae, such as the Type 1a supernova he and fellow astronomers including Ben Dilday discovered (2), are capable of producing the very iron in our blood and the calcium in our bones is created.

|

| Credit: Neven Mrgan |

While the astronomer discussed the nature of "alchemy," or the fusing of matter into atoms and elements, and how each of these elements (e.g. calcium) shoot out from exploding stars, I could only fixate my attention on the sobering fact that every particle of matter in me and an apple pie (carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, calcium, iron) was produced in a supernova in the same way.

And, the eloquence of that celebrated man came to mind, because of one other wonderful thing he famously said. This quote should be cherished by all scientists -- chemists, astronomists, biologists, and food scientists alike:

"The nitrogen in our DNA, the calcium in our teeth, the iron in our blood, the carbon in our apple pies were made in the interiors of collapsing stars. We are made of star stuff."

References

- Crawford M and Marsh D. Nutrition and Evolution. New Canaan, Ct: Keats Publishing; 1995.

- Dilday B, Howell DA, Cenko SB, et al. PTF 11kx: A Type Ia Supernova with Symbiotic Nova Progenitor. Science 24 August 2012: 337(6097);942-945. DOI: 10.1126/science.1219164

Labels:

carlsaganday,

sciwri12

Wednesday, November 7, 2012

Why lemurs get sick: A lesson for humans, too

|

| Female blue-eyed lemur |

This was the question on my mind as I toured the Duke Lemur Center in Durham, North Carolina with colleagues attending Science Writers 2012. (Read Christie Wilcox’s full report about our tour over at Science Sushi on Scientific American.)

When I learned on the tour that lemurs were getting sick, I inquired further from our tour guides, education associate Chris Smith and education manager Niki Barnett. The thought of these adorable creatures—somehow related to me because of a common ancestor some 50 to 80 million years ago—suffering from the same types of chronic diseases as modern-day humans encouraged me to want to find out more about their care and treatment.

Lucky for me, Chris, who might’ve tired from me badgering with so many questions, helped me arrange an interview with the center’s senior veterinarian. On my second visit to the center at a later date, Dr. Cathy Williams described for me, and showed me, what it was like to work as a clinician in the world of lemurs.

Lemurs and humans, not so different

There are multiple parallels between why humans get sick and why the lemurs do, Dr. Williams told me.

Lucky for me, Chris, who might’ve tired from me badgering with so many questions, helped me arrange an interview with the center’s senior veterinarian. On my second visit to the center at a later date, Dr. Cathy Williams described for me, and showed me, what it was like to work as a clinician in the world of lemurs.

Lemurs and humans, not so different

There are multiple parallels between why humans get sick and why the lemurs do, Dr. Williams told me.

"They mainly have to do with diet," she said. The diets for lemurs at the center are not necessarily ideal—even in this magical place, home to the largest population of the world's most endangered primates outside of Madagascar.

Routine physical exams and dental cleanings make up most of a day in the life of a senior veterinarian, Dr. Williams told me. The veterinarians and keepers work hard to make life for the lemurs as healthy and comfortable as possible.

|

| Sifakas eat primarily leaves |

"There is less fiber, the fruits are softer, and there’s less chewing and pulling leaves from trees," Dr. Williams said. Chewing and pulling in the wild act as nature’s way of brushing and flossing, Dr. Williams said, "We see a lot of gum diseases. I’ve never seen that in the wild at all."

Dental care

Lemurs in the center receive dental cleanings every couple of years. If one of the animals has dental problems, they get cleanings more often. Dr. Williams also encourages behavioral trainers to regularly floss the teeth of the lemurs, time and human-power permitting.

Similar to lemurs, dental caries are somewhat of a novelty among humans, according to Randolph Nesse and George Williams. The authors of Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine wrote that tooth decay and cavities only became more common because of today’s frequent and prolonged exposure to starches and sugars that feed the bacteria responsible for producing acid that causes demineralization of teeth.

Caries exist in alongside a long list of chronic health-related problems caused by "modern dietary inadequacies and nutritional excess," Nesse and Williams write. Others we're all familiar with are obesity and diabetes.

Choosing appropriate foods

|

| Blue-eyed lemurs and sifaka play together, but have different diets. |

Because the center is in the habit of loaning animals out to other zoos around the country, they've seen obesity become a problem in part because of the difficulty in training zookeepers on how to appropriately feed the lemurs appropriately.

The major challenge, she said, is in simply educating keepers to understand that feeding strategies are different for different species of lemur. All lemurs are similar in that they are herbivorous hindgut fermenters having simple stomachs and large cecums (as opposed to foregut fermenters, which are generally ruminant species like cows); however, intestinal transit times between lemurs vary greatly.

On one end of the spectrum, you have the red-ruffed lemur. In this species, the intestinal transit time is short, so fermentation in the cecum is bypassed. Their feeding strategy is to eat easily digestible foods, and a lot of them. They primarily eat a lot of fruits, but don't absorb a lot when they do. "The joke goes: it goes in a banana, it comes out a banana," Dr. Williams said.

On the other side of the spectrum, there are bamboo lemurs and sifakas with long intestinal transit times. These lemurs eat primarily leaves and rely on their fermentation for production of short-chain fatty acids to supply the majority of their energy (similar to gorillas versus chimps). In comparison, the ring-tailed, brown and blue-eyed lemurs tend to be more generalist in eating a variety of leaves, fruits, and some insects. Ring-tailed lemurs may even make a meal out of a small bird on occasion.

Many of the problems result from insufficient knowledge or misunderstanding on the part of zookeepers. If a red-ruffed lemur is put on a diet of leaves, the animal won't absorb enough nutrients to survive for very long. Conversely, if a sifaka is fed a diet high in fruit, the diet will favor growth of microflora that uses starch more efficiently and doesn't ferment fibers well; the resulting changes in pH alone will give the animal diarrhea until its probable death.

Many of the problems result from insufficient knowledge or misunderstanding on the part of zookeepers. If a red-ruffed lemur is put on a diet of leaves, the animal won't absorb enough nutrients to survive for very long. Conversely, if a sifaka is fed a diet high in fruit, the diet will favor growth of microflora that uses starch more efficiently and doesn't ferment fibers well; the resulting changes in pH alone will give the animal diarrhea until its probable death.

To prevent sickness and death of animals that are on loan, Dr. Williams said zookeepers are now required to come to the center to be trained, "They'll learn that, yes, sifakas like banana, but, no, we can't feed it to them. Yes, they will eat it, but it's not good for them."

Controlling portions and low-glycemic foods

|

| Ringtailed eat a mix of fruits, leaves, insects, and even birds. |

One important bit of knowledge Dr. Williams passes on is that "when we say 'frugivore,' we're talking about a wild diet that is very high in fiber, low in starches. But when folks think 'frugivore' in captivity, they think apples, bananas, and grapes—these are not at all like fruits in the wild."

Lemurs at the center are never overfed, Dr. Williams told me, but diabetes is still a significant issue. "The diabetics in our colony were never obese, but we're still causing problems that lead to insulin resistance," she said. In addition, kidney failure and cancer are other main causes of death.

Much in the same way humans might like "marshmallows and chocolate eclairs," as Nesse and Williams write in their book, the problem with lemurs is that they have "mismatch of tastes evolved for stone age conditions."

All lemurs enjoy the types of fruits and starchy vegetables we've cultivated for our taste buds, Dr. Williams said, which can easily lead to overfeeding with these kinds of foods and that can lead to obesity and diabetes.

Lemur care, age, and inflammation

Once an animal has diabetes, it must be controlled with a low-glycemic diet—consisting of leaves and primate biscuits that are higher in fiber, lower in starch and sugar—alongside anti-diabetic medications such as metformin.

All lemurs enjoy the types of fruits and starchy vegetables we've cultivated for our taste buds, Dr. Williams said, which can easily lead to overfeeding with these kinds of foods and that can lead to obesity and diabetes.

Lemur care, age, and inflammation

Once an animal has diabetes, it must be controlled with a low-glycemic diet—consisting of leaves and primate biscuits that are higher in fiber, lower in starch and sugar—alongside anti-diabetic medications such as metformin.

I asked Dr. Williams how the lemurs responded to being put on their low-glycemic biscuits versus their normal, more palatable, sugary, cookie-like treats. She said they responded in the same way as a human would after hearing, "OK, you're not eating anything but bran and leafy greens for now on." Not very well at all.

There are several contributing factors to chronic disease in lemurs, Dr. Williams said. One may be simply be age, since the animals at the center, depending on the species, can usually live well into their 20s and 30s, which is not normal in the wild.

These older animals also have limited mobility, resulting from age-related wear and tear, and are not able to enjoy some of the free-range enclosures the lemur center provides. A more sedentary lifestyle indoors can lead to less insulin sensitivity and, while the center does offer enrichment programs to encourage activity, Dr. Williams notes, the rewards used in these programs is usually sweet treats.

Seeking the ideal lemur diet

Seeking the ideal lemur diet

How these aging lemurs are fed and what they're fed in their diets are still not what Dr. Williams would consider ideal. "It could be better," she said; for instance, the lemurs usually receive all their food in one or two feedings daily while, in the wild, they generally graze throughout the day. More feedings over the course of the day may help stabilize blood sugar.

In addition, Dr. Williams has noted mild, low-grade inflammation is a factor. As part of her clinical duties, she performs autopsies whenever a lemur dies. Histopathological exams of tissues upon death often reveal a mild chronic colitis or hepatitis. "We don’t know what the cause is," Dr. Williams told me.

One possible contributing factor, Dr. Williams told me, may be in the type of ingredients used in the flavored primate biscuits or other foodstuffs the lemurs eat. The biscuits are primarily grain-based, she said, containing corn, soy, or wheat to provide one source of starch, soluble fiber, and insoluble fiber, along with protein sources.

Ideally, she said, a lemur's diet should consist of diverse types of fiber found in the same types of wild fruits and vegetables found on Madagascar. These could include several types of pectins, gums, and other fermentable fibers. Another area of concern may be omega-6 to omega-3 ratio of the lemurs' chow.

Ideally, she said, a lemur's diet should consist of diverse types of fiber found in the same types of wild fruits and vegetables found on Madagascar. These could include several types of pectins, gums, and other fermentable fibers. Another area of concern may be omega-6 to omega-3 ratio of the lemurs' chow.

Education outreach and lemur nutrition research

|

| Dr. Williams |

After my interview with Dr. Williams, I contacted Michael Schlegel, Ph.D., director of nutritional services for the Zoological Society of San Diego to discuss her recommendations. Dr. Schlegel's role is to formulate meals for all the animals in at the San Diego Zoo and supervise how they are fed.

Dr. Schlegel found Dr. Williams's findings highly interesting, saying, "We're always looking for new research and we do balance diets so that fruit is only a component. They do get vegetables, but we know more is what's good for them."

Zoo keepers and zoo nutritionists like Dr. Schlegel rely on guidelines given by the National Research Council's Nutrient Requirements of Nonhuman Primates, much as Americans rely on Institute of Medicine for dietary guidelines.

"We look at publications, and adjust to individual needs. We try to base diets on animal energy and metabolic requirements," he said.

Schlegel agreed that current dietary requirements for all primates are based on limited studies. Further research is needed in areas such as analysis of dietary composition of wild diets as well as controlled trials with lemurs as a species.

As it stands, the science of nutrition and diet is still young for humans and lemurs alike, but so far the similarities on how the modern world affects human health and how captivity affects our far distant cousins are striking.

Labels:

Evolving Health,

sciwri12

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)